Strategy for Buying OPTN Tech

Overview of Acquiring Digital Services for the OPTN

The life-saving system of organ donation and transplantation in the U.S. is coordinated through the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) contract with the federal government. For more than thirty years, this contract called for competencies in both the coordination of the organ donation and transplant ecosystem, and also critical support for the technologies that underlie the system.

“We don’t have the in-depth IT staff to have an understanding whether the things are being built are good.”

- HHS Official

The current procurement processes in place hamper the government’s ability to truly support organ donation reform and do not reflect procurement best practices. The following documents outline the problems in previous and current OPTN procurements and offer recommendations to support a new approach for buying digital services. A contract with a vendor that delivers digital services that embodies modern procurement practices could indeed translate into saving more lives and taxpayer dollars.

“The OPTN contractor has devolved into a hostage-taking situation, where it has convinced the government that no one else can do what it does, but it doesn’t perform its functions particularly well.”

-Transplant Surgeon

Our included documentation:

BACKGROUND & METHODOLOGY

Researchers, including former government experts, were brought in to conduct research around the processes, systems, and technology on which the organ transplant system has been built and continues to run. We interviewed more than 30 people within the organ donation system, including OPO leaders and staff, organ specialist consultants, donor hospital staff, transplant surgeons, government officials, and researchers. We also interviewed digital service vendors who offered special insight into procurement and technology best practices. This report is based on those interviews, case studies, and existing research, as well as the OPO Best Practices and Tech Recommendations reports compiled by our researchers.

Procurement Strategy

For several decades the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) contract has included scope for both coordination work for the organ donation and transplantation ecosystem as well as the technology that supports that coordination. When it comes to organ donation reform, it is important to have a buying approach that best supports that reform. This includes the government partnering with vendors who have core competencies in coordination, which are different from the vendors who have a core competence in digital services.

Through our team’s research, it has become abundantly clear that the current OPTN contractor has been unsuccessful at both scopes. Since the research team’s competencies are service design and digital services, we focused on a new procurement which would only include scope for digital services related to organ donation. The aim of this document is to eventually lead to a contract that enables, facilitates, and incentivizes digital services delivery with a vendor awardee that embodies and predominantly undertakes practices from the Digital Services Playbook. As one part of the research process, we interviewed five non-traditional vendors to understand potential barriers to entry for winning this procurement and gain insight around what would level the playing field for new, non-traditional vendors to bid for the OPTN technology work.

The documented approach is represented in the TechFAR Hub, as well as part of the Government Accountability Office’s (GAO) Agile Assessment Guide and focused on outcomes above prescribed technical features. This approach is specifically applied to the organ donation and transplantation ecosystem through our research, and the result is represented here.

Erosion of Government’s Leverage

The government currently finds itself in a situation of little leverage compared to the OPTN contractor’s high leverage. This makes it extremely difficult for the government to achieve a fair business deal using a contract. As indicated immediately below, there are numerous forces that have contributed to the government’s low leverage, some dating back to over thirty years ago.

- National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) of 1984 limiting Govt’s ability to innovate, 1984

- Govt’s accepting vendor’s intellectual property (IP) rights which creates vendor lock-in, 1986/first UNOS contract, though IP rights ownership happened later

- Renewing contracts to poor performers, numerous times, most recently 2018

- Atrophy of Govt’s technical acumen, 2001-2020

- Contracting’s ineffectiveness in creating competitive pressures, each renewal

- Inexperience with buying digital services, 2020-present

Due to this imbalance, the Government finds itself at a significant disadvantage when striking an equitable deal with the existing OPTN vendor. As part of the proposed approach to buying, we focused on what would facilitate a significant rebalancing of that power.

The OPTN contract has been re-awarded, since its beginning, to the same vendor.1 This has included a multi-year sole-source award at the end of one contract, and during a separate procurement recompete there was just one bid received (from the existing contractor). From a procurement operations perspective, the process executed appears to follow all of the procurement regulations. From the perspective of procurement best practices and optimizing around competition, our research found very little substance. As a result, we have developed an approach that will significantly increase competitive pressures and solve other systemic problems identified in the existing contracting for organ donation work.

Problems to Solve In Buying OPTN Technology

Our research uncovered a number of problems with the current and previous OPTN procurements, which are listed immediately below. The team developed an approach that aims to solve these problems. The list below is not intended to be comprehensive of all issues addressed within this strategy but it highlights some of the prominent challenges we have identified.

- Wrong Objectives: The objectives from the existing contract do not support doing the most good for the most amount of people (in the organ transplant space)

- Short Proposal Window: The 31 days to submit a complete proposal has been inadequate for vendors to compete well (except for the incumbent)

- Technology Poverty: The technology is characterized by slow delivery of new features and lackluster security

- Unempowered End Users: End users have small voices when it comes to communicating problems to those who can best solve those problems

- Government’s poor leverage: Existing technology is proprietary and therefore difficult for non-incumbents to improve upon

- Non-Profits Only Awarded: 42 US 274 prescribes awarding to a non-profit

- Past Performance / Corporate Experience: 42 USC 274 indicates that the vendor shall have expertise in organ procurement and transplantation

A Strategic Procurement Pivot

Since the advent of the agile manifesto, modern technology development approaches have significantly advanced. This involves incremental approaches to developing software in rapid agile cycles while gaining frequent feedback from end users. Only a non-traditional procurement approach can effectively support and leverage the benefits of modern technology practices. Done poorly, a contracting approach can easily block the delivery of digital services. Done well, a digital service contracting approach facilitates both (1) awarding to a modern technology vendor and (2) providing appropriate flexibility and incentives in the contract that enable — not strangle — innovative approaches to solving problems using digital services.

Traditional IT Procurement vs. Digital Services Procurement

Traditional information technology (IT) procurement involves establishing plans to have vendors build technology in an antiquated way - in fact, the way that was common 30+ years ago. While the research team did not have access to the base code of the existing systems involved in organ procurement, architectural diagrams and interviews point to an outdated set of systems developed decades ago. During one research interview, a leading healthcare technology executive described the incumbent’s technology inner workings, such as ranking algorithms, as “literally duct tape.” Numerous interviewees indicated a poor user experience with organ placement technology, and several complained that it takes the contractor 12+ months to deliver new, yet relatively small, features once those features are mandated by federal regulation. We found little evidence that the existing OPTN contractor either engages closely with, or develops technology closely with, end users.

We’ve made several specific suggestions to help move the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) and the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) from a traditional government IT buying approach to a digital services buying approach for OPTN tech. This includes allowing for more innovation by using a Statements of Objectives, and using a clear problem statement and product vision to guide the overall efforts for the OPTN technology work.

Implementing an Acquisition Strategy Focused on Objectives

Statement of Objectives

A Statement of Objectives (SOO) provides basic, high level objectives of the acquisition and is the least prescriptive choice of a requirements document. It allows industry to re-imagine innovative approaches to achieving the objectives related to organ donation reform. The SOO opens up the acquisition to a wider range of potential solutions. While the SOO is included in the Request for Proposals (RFP), it will not be a part of the eventual contract. In response to the SOO, vendors submit a technical approach in the form of a Statement of Work (SOW) which clearly describes the performance objectives and standards that are expected of the vendor.

Problem Statement

More unusual, although helpful, is including a problem statement in the RFP. A clear and concise problem statement provides a laser focus for the problem solvers - the digital service vendors. In a government procurement, both the government and the contractor should be driving towards solving the same problem. The problem statement, just like the Statement of Objectives, should use plain language so that as many people as possible can grasp the concept without further explanation. This also helps define the project scope, which keeps the project concentrated on the overall goal.

Product Vision

Up to this point, the OPTN contract scope has been too prescriptive about the technology to be built and maintained. This traditional approach to government procurement typically limits innovation only to those solution ideas created by a few people in government involved in the procurement. A Request for Information (RFI) asking for a written response can, if constructed well, provide some additional ideas from industry to government. However, the exchange as a result of an RFI typically results in very small changes to the overall level of innovative ideas since the final Performance Work Statement or Statement of Work remains prescriptive in terms of technology approach.

The product vision is the overarching goal of the technology product/solution. It provides the target customer, a statement of need, the product name, the product category, the key benefit, the primary competitive alternative, and makes clear what makes the digital product primarily different. This product vision should be the technology scope for the OPTN technology contract. It should be clear and accurate. It also provides the ultimate goal for all the work to be performed. When combined with vendor submissions that propose a modern technology process (as opposed to locking in technical features at the contract level), the government (partnered with the awarded vendor) have tremendous flexibility to iteratively build a technology product that can evolve at the pace of end users needs.

Buy a repeatable process, not predefined technical features

For some procurements, the problems to solve are simple, there is a deep understanding of end users, and details about the existing technology are transparent. In those cases structuring a procurement around predefined features may be most appropriate. An example is buying a ubiquitous technology such as an email solution. The government can expect several existing and competitive products available in the market.

This is not the case with organ donation. The problems to be solved are complex. There is still much to be learned about the end users and their problems. Their problems have and will change over time. Visibility into the existing technology is opaque at best. In those situations, it is critical to contract for a vendor that excels at modern technology best practices such as the Digital Services Playbook. Those vendors follow an iterative, yet mature, repeatable process for building modern technology, such as agile software development. The vendor’s repeatable process, which delivers working software every few weeks, should be explained in great detail in the vendor technical proposal and is at the core of the contract scope (not the technical scope, which is the Product Vision).

By buying a repeatable process that delivers working software, the government is not contractually locked into buying technical features defined pre-contract which it assumes solves end users’ problems. Buying a repeatable process provides a way to get working software into the users of OPTN tech, get their feedback every few weeks, and then rapidly pivot and change or enhance those features within a few weeks to validate whether or not the technology solves their problem. This process provides a structured approach to release software into production frequently, which is a cornerstone of agile software development. In contrast, the existing OPTN vendor typically takes upwards of 12 months to deliver new features into their production environment.

Down-Select

Previous OPTN procurements required vendors to submit all parts of the proposal together at once. This traditional procurement approach requires high business development costs, while vendors receive little, if any, indication of their chances of award until the government has made an official contract award decision. Small businesses, with their limited business development budgets, find the approach especially burdensome.

The down-select process is a very powerful tool in the agency’s acquisition toolbelt that saves time for both the government and vendors. The down-select is a phase in the procurement lifecycle that requires the evaluation of some information (for example, past experience, technical skill sets) to determine the likelihood of a vendor’s success in winning the contract. The down-select can be either mandatory or voluntary. The initial phase of a down-select should involve low business development cost yet be effective at eliminating vendor’s who’s probability of winning the contract award is low. Through later phases of the down-select, the increased business development cost is commensurate with a higher likelihood of award. Our research indicated that small businesses favored the down-select approach for the OPTN technology procurement.

When the government gives transparent feedback to vendors throughout the process — including when some proposals have a low probability of winning — this allows vendors to decide whether they want to put more time and resources into the procurement process. For this procurement, we recommend the following down-select process:

- Case Studies

- Design Challenge

- Written Technical Approach, Price Submission, and Offer & Award Documents, Certifications and Representations

Case Studies

Case studies can provide vendors a light weight initial submission in a multi-phase down-select. As opposed to a traditional past performance submission, the vendors for OPTN tech should be directed to submit case studies from work performed by their company to deliver digital services. Vendors with inexperience in digital services will struggle to provide a sufficient story, which leaves an opportunity for the government to communicate to such a vendor that they are unlikely to receive an eventual award and therefore strongly discourage their continued pursuit of the OPTN tech award.

Design Challenge

The previous OPTN procurements only allowed for written proposal submissions. This traditional government procurement approach does not force vendors to show how they can perform the work. It allows vendors to make assertions in a proposal while making it difficult for the government team to validate those assertions within the procurement process itself. As an example, in the 2018 RFP charges the vendor to “Develop innovative applications to enhance the matching function used by OPTN members” (Performance Work Statement section 3.4.2). However, the procurement strategy did not include an effective way for the vendor to simulate, or show in some way, how the company would deliver modern technology, let alone innovation. Our research only found evidence of poor, outdated technology practices from the contract awardee.

Conversely, a design challenge provides a “show, don’t tell” in the procurement and is a tool that has proven effective in removing digital service vendor imposters during the procurement. The design challenge is arguably the single most important part of the procurement evaluation process. Because each procurement is different, the design challenge for OPTN technology needs to be customized to align with the key components of the Statements of Objectives.

To get the most accurate insight into each vendor’s ability to successfully execute against the product’s objectives, the government needs to craft a challenge that closely matches the type of work that will be involved in the product development. If the procurement is for a very technical product or service, the challenge should be technical. Alternatively, if the procurement will be product management heavy, the challenge could include building out a product roadmap with prioritized milestones.

The government will need to come up with a realistic scenario that vendors can respond to with either working software, design artifacts (for example, wireframes), product management approaches (for example, product milestones and backlog of prioritized work), or any other range of artifacts that will be essential for the specific procurement.

Revisit Past Performance

42 USC 274 indicates that the vendor shall have expertise in organ procurement and transplantation. This dictates that an Offeror’s past performance in this expertise must be evaluated as part of the proposal. The 2018 RFP specified that vendors would be evaluated on, “The Vendor (organization) experience… in the field of organ transplantation based on a minimum of 3 years of corporate experience in managing projects of similar scope and complexity in the field of organ transplantation.”

We had difficulty identifying leading technology vendors in the organ transplantation space that managed similar scope and complexity to the scope of the requirement/contract. This requirement has contributed to HRSA’s lack of meaningful competition. In addition, modern technology vendors have the ability to coordinate highly complex situations including organ donation transplantation. We recommend the following changes:

- Eliminate the minimum amount of years of corporate experience in the specific organ transplantation field

- Indicate that vendors with no experience in the field of organ transplantation receive a neutral score for past performance

- Structure the past performance technical factor as far less important than any other Technical Factor

The last recommendation regarding relative importance is especially critical. The government is communicating that past performance must be evaluated in some way, shape or form but overall the government sees past performance as having little importance when it comes to which vendor can receive the contract award. Therefore whether a vendor’s past performance in this specific area is strong or weak, it is of little consequence to the ultimate decision for who will receive the award. The suggested changes above, when combined, will effectively neutralize organ placement past performance from being a barrier to entry for competitors for the OPTN technology work. The past performance requirement seen in previous OPTN procurements will no longer dissuade vendors from providing effective competitive submissions.

Vendor Pool

The technology scope of the OPTN contract has been fulfilled by one vendor. Our research indicates the vendor maintains an antiquated technology and limited technical acumen. We suggest contracting with a vendor that embodies modern technology approaches such as the Digital Services Playbook. Most of the companies that excel at digital service delivery in government are still small businesses.

The incumbent vendor asserts that they are the only company capable of providing the technology solution. However, our research—which included analysis of current technology, user research interviews, as well as interviews with digital service vendors–found that several other vendors can and are willing to deliver superior technology. Due to the size and scope of work to be performed, we believe that contracting with multiple vendors will be most advantageous since a single digital services vendor does not have core competencies in all relevant areas necessary to solve the technology problems identified.

For example, a technology company with core competencies in building technology infrastructure usually does not also have a core competency in human centered design. However, both are critical to building a successful digital product for organ donation. Therefore, a procurement approach that gives the government easy access to multiple vendors, with complementary core competencies, will position the government best for building the desired product.

We recommend the use of a Blanket Purchase Agreement (BPA). The government first conducts an initial competition to establish a small pool of pre-qualified vendors that excel at digital service delivery. Once awarded, the government conducts smaller, rapid competitions for individual task orders. Using a BPA, the government can expect similar benefits to those from CMS’s Quality Payment Program (QPP) BPA: low/zero award protests, average procurement action lead time is 67 days, 2-week RFP release to submission cycle time, and flexibility to change vendors more quickly.

While a BPA has many strengths, it is a tool that must be wielded by capable talent. Failure is likely in the hands of a government team inexperienced at managing digital teams and coordinating multiple vendors building a common digital product. However, when the government team is high functioning, has modern technology skills and system integration management skills, the BPA can offer the team tremendous flexibility and capacity to rapidly deliver modern technology compared to traditional government technology implementations.

Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan (QASP)

A QASP consists of a roles and responsibilities section that describes the formal relationship between the vendor and the government’s contracting specialist/officer. It will also describe the performance metrics the vendor will adhere to based on their proposal, which describe how the government can verify each metric.

While the roles and responsibilities included in a QASP tend to be fairly static across modular procurements, the performance metrics should both be generic as well as tailored to the product that’s being delivered by the vendor. A good QASP will have objective-based performance metrics. These performance metrics can come in many forms, including progress towards a desired result, the dependability of something, or the security of a system.

The measurement of these performance metrics is important, and measuring them should be easy. Due to the poor metrics and lack of accountability in the current OPTN contract, a strong QASP will serve as an important motivator to perform well under the new contract. While the 2018 OPTN RFP included a QASP, it provided a very low standard for the technology provided. Our team instead provided a QASP in the draft RFP that demands the vendor’s excellence in modern technology practices.

Pricing Structure

Our research found that HRSA’s contracting of IT services usually used a price structure that is cost type. Cost type contracts require rigid cost accounting standards from the vendors which are most appropriate for research and development contracts - especially for scope related to non-commercial items. That is appropriate for building tanks, but modern technology services were developed in the private industry and therefore commercial services. Therefore pricing structures more common in the commercial industry are more appropriate, including labor hours/time and materials or firm fixed price.

Basis for Award

Similar to the majority of government IT procurements, the 2018 OPTN RFP included a tradeoff between Technical Factors and Price, which considers the mix between technical and price to arrive at an overall best value determination. The 2018 RFP indicated the technical proposal (excludes price/cost) when “combined they are significantly more important than the Cost Factor.” But this approach means that the Government may have to sacrifice the best technical proposal for a proposal with a lower price.

Digital service vendors deliver some of the best technologies in government, yet oftentimes provide pricing higher than average government IT vendor pricing per hour. There are a number of factors contributing to this, most importantly is the vendors’ compensation plan which is critical to attracting and retaining talent from Silicon Valley. The government should consider however, the total lifecycle costs for the technology delivered, as well as the value provided by a digital services vendor when compared to traditional government IT vendors.

One digital service vendor interviewed by our team indicated that development of scalable, flexible, architecture may be very high during years 1 and 2 of a project (especially because of senior level architects required by the vendor). But after that first year or two, the costs to maintain well built infrastructure as a service is very low compared to traditional government IT vendors. In addition, well built modern infrastructure is a key ingredient to future-proofing the overall technology solution.

Since the best digital service vendors may have higher hourly rates than traditional government IT vendors, it is incumbent upon the government to communicate how superior technical approaches significantly overshadow proposed labor hours price. An effective means of wiring this value at the tactical level of the procurement involves adjusting the Basis for Award to indicate the following:

- There is no tradeoff between any of the Technical Factors and Price

- The Offeror’s price must be fair and reasonable

Our suggested approach above decreases the risk of forcing the Government’s hand to award to a vendor with lower than the best technical score - which is usually a competitor who has less technical capability but has underbid the price in a way that endangers sustained product delivery. The suggested tactic allows the Government to let only the highest technically rated proposal make it ‘over the bar’ to be considered for pricing. The Government will then determine whether the vendor with the highest technically rated proposal also has pricing that is fair and reasonable. The government should be careful to consider whether the pricing is fair and reasonable according to the commercial industry including the high tech labor market, not simply comparing the proposed labor rate to government sector pricing such as the average hourly rate found on the GSA Calc tool. If the price is not found to be fair and reasonable, the Government will repeat that determination for the next highest technically rated proposal. This approach provides the Government a way to more easily contract with the vendor with the highest technical score – the vendor that can do the work best.

Notes

Draft Request for Proposal

Background

The purpose of the previous Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) was to provide both coordination efforts as well as a supporting technology solution. The purpose of the OPTN is to coordinate and improve the effectiveness of the nation’s organ procurement, distribution and transplantation systems and to increase the availability of, and access to, donor organs for patients with end-stage organ failure. The OPTN was established pursuant to the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) of 1984. The functions of the OPTN are described in statute (42 USC 274), and the OPTN final rule (42 CFR 121) provides further clarification of the structure and functions of the OPTN.

Moving away from the previous contracting strategy, this procurement does not include scope for coordination efforts but does include the technology scope previously in the OPTN contract. This multiple award Blanket Purchase Agreement (BPA) will conduct the technology operations of the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN).

The below reports provide more context about organ donation.

- Reforming Organ Donation in America, Bridgespan, 2019

- The Costly Effects of An Outdated Organ Donation System: Summary of Findings

Introduction

The objective of this procurement is to award a multiple award BPA to provide HHS/HRSA agile product design and delivery services to accomplish the Statement of Objectives. While traditional government technology vendors are capable of making nominal improvements (eg. 1.3X) to effectiveness, the government desires vendors that embody the Digital Services Playbook, who are more capable of re-imagining approaches and delivering solutions which improve organ donation effectiveness by orders of magnitude (eg. 10X).

In addition, the government needs a vendor that delivers solutions using modern technology approaches which de-risks the chance of a failed project. The desired vendors use modern technology approaches to learn and pivot rapidly. The government is not interested in a traditional technology vendor that plans to deploy working software 1.5 to 2 years after the award. The government does want a digital services vendor, when combined with the appropriate support from the government, that will deploy working software minimum viable product into production within 6 months of award. Following MVP delivery, the Government desires the product team to continue to iteratively deliver additional functionality (while lowering/maintaining technical debt) that will help solve the problems most important to the end users which were identified most recently.

This effort is consistent with several initiatives to strengthen Federal acquisition and technology practices, such as:

-

The Digital Services Playbook, released by OMB in August 2014, as a best practices guide for agencies to use when developing effective digital services; and1

-

The TechFAR Handbook, released by OFPP in August 2014, as a guide to the procurement of agile design and development services within the Information Technology (IT) Consulting, IT Outsourcing, and IT Security Categories.2

Problem Statement

Donor hospitals, transplant center technicians, organ procurement organizations, researchers and health agencies experience difficulty during the organ donation process and are frustrated by:

- Technical capabilities failures,

- Lack of clinical agility,

- A bad user experience,

- Deficiencies in identifying potential donors,

- Bias that leads to refusal of viable organs,

- Organ waste and inefficiencies with transplants not maximized,

- Compounding costs

Product Vision / Scope of Contract

The below product vision is also the overall scope of the contract.

For donor hospital and transplant center clinicians, organ procurement organizations, researchers and health agencies who need to efficiently and clinically match donor organs with transplant candidate recipients across the nation, and to make continuous improvements to that system the ModernOrganSystem is a matching technology that tracks donor hospital referrals, house recipient candidate information (waitlist), matches organs using clinical algorithms, and logs all transplant outcomes unlike DonorNet our product increases transplants in the US and reduces mortality and costs.

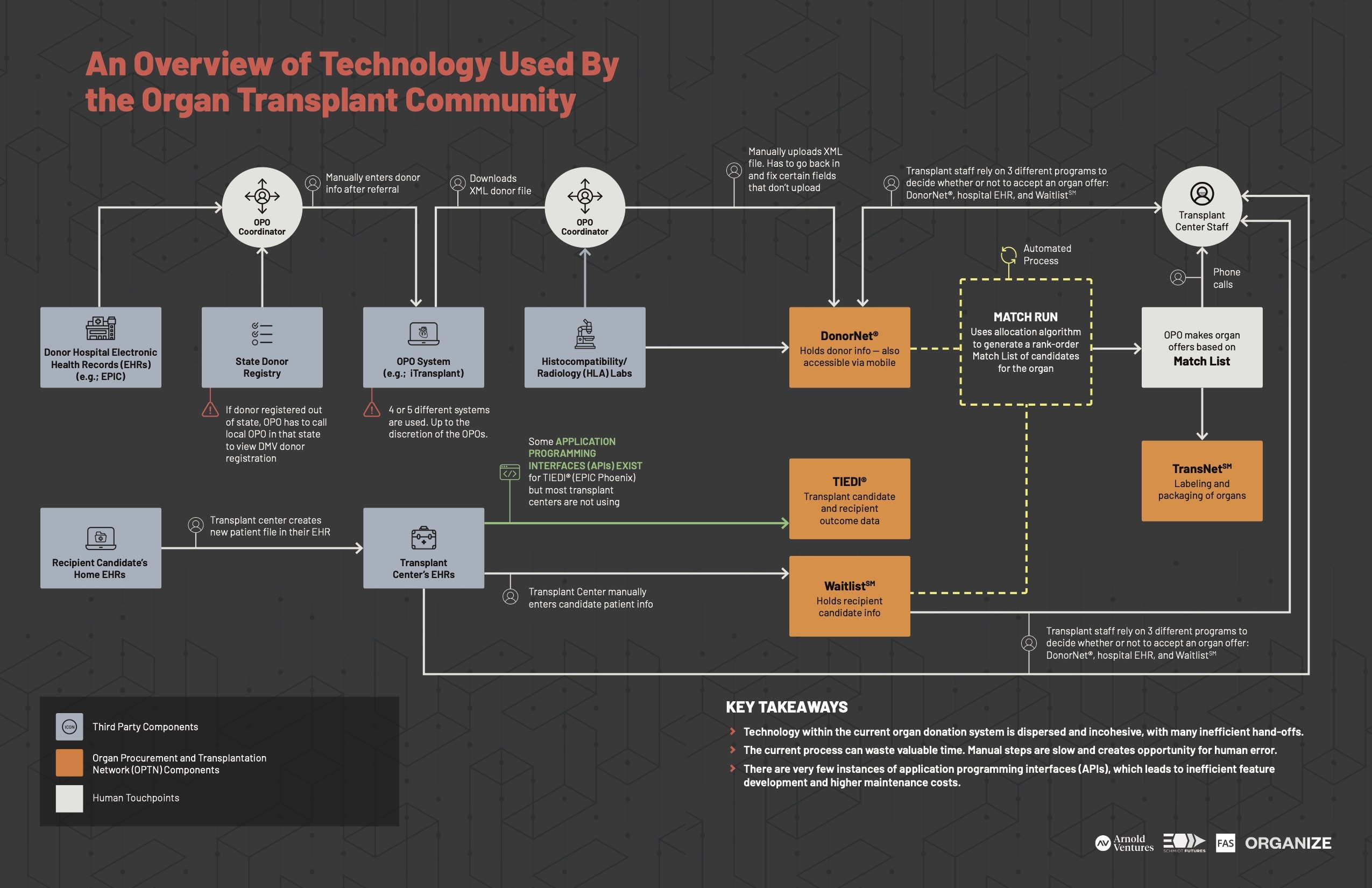

Process map

Figure 4

Download the “How an Organ is Managed (Or Not) in the Current Organ Donation System” PDF

Current Technology

Figure 6

Download the “An Overview of Technology Used By the Organ Transplant Community” PDF

Statement of Objectives

See Attachment 1c.Requirements Document

Applicable Documents

The Contractor shall comply with the documents listed below. (HHS/HRSA to include relevant documents, such as clauses or information security standards)

- Lorem ipsum

- Lorem ipsum

- Lorem ipsum

General Requirements

The Contractor shall provide and/or acquire the services, hardware, and software pursuant to the general requirements specified below.

Contract Type

This is a multiple award Blanket Purchase Agreement (BPA) awarded using Federal Supply Schedule / GSA Schedules Program (FAR Subpart 8.4), more specifically using GSA Schedule 70. This requirement is set-aside for small business concerns. The contract shall be issued on a performance-based T&M/Labor Hour and/or FFP basis. Once the BPA is awarded, smaller requirements will be competitively awarded among the BPA awardees.

Period of Performance

The period of performance for this contract includes a 12-month base period and four (4) 12-month option periods.

Hours of Work

Work at a Government site shall not take place on Federal holidays or weekends unless directed by the CO. The Contractor may also be required to support 24/7 operations 365 days per year as identified in individual Task Orders.

There are ten (10) Federal holidays set by law (USC Title 5 Section 6103) that the Government follows. Under current definitions, four are set by date:

- New Year’s Day - January 1

- Independence Day - July 4

- Veterans Day - November 11

- Christmas Day - December 25

If any of the above falls on a Saturday, then Friday shall be observed as a holiday. Similarly, if one falls on a Sunday, then Monday shall be observed as a holiday. The other six are set by a day of the week and month:

- Martin Luther King’s Birthday - Third Monday in January

- Washington’s Birthday - Third Monday in February

- Memorial Day - Last Monday in May

- Labor Day - First Monday in September

- Columbus Day - Second Monday in October

- Thanksgiving - Fourth Thursday in November

Place of Performance

It is expected that contractor’s teams will be required to frequently interact with system users and program staff in support of this agreement. The contractor’s teams may do so primarily remotely. During the instances when the contractor’s team may need to travel associated with the scope of this contract, the government anticipates that most of the work will occur in the contiguous United States (CONUS).

Travel

When travel is required, travel details must be provided to, and approved by, the Contracting Officer’s Representative (COR) or the Government designee prior to the commencement of travel. All travel shall be in accordance with the Federal Travel Regulations (FTR).

Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan

This Quality Assurance Surveillance Plan (QASP) will define the performance management approach taken by the Government to monitor and manage the contractor’s performance to ensure the expected outcomes or performance objectives communicated in the SOO are achieved.

| Deliverable | Performance Standard(s) | Acceptable Quality Level | Method of Assessment |

| Tested Code | Code delivered under the order must have substantial test code coverage and a clean code baseVersion- controlled, public repository of code comprising the product, which will remain in the government domain | Minimum of 90% test coverage of all code | Combination of manual review and automated testing |

| Properly Styled Code | GSA 18F Front-End Guide | 0 linting errors and 0 warnings | Combination of manual review and automated testing |

| Accessibility | Web Content Accessibility Guidelines 2.1 AA | 0 eros reported using an automated scanner, and 0 errors reported in manual testing | Pa11y |

| Deployed | Code must successfully build and deploy into staging environment | Successful build with a single command | Combination of manual review and automated testing |

| Documented | All dependencies are listed and the licenses are documented. Major functionality in the software/source code is documented. Individual methods are documented inline using comments that permit the use of documentation-generation tools such as JSDoc. A systems diagram is provided. | Combination of manual review and automated testing, if available | Manual review |

| Security | OWASP Application Security Standard Verification Standard 4.0, Level 2 | Code submitted must be free of medium- and high-level static and dynamic security vulnerabilities | Clean tests from a static testing SaaS (such as npm audit) and from OWASP ZAP, along with documentation explaining any false positives |

| User Research | Usability testing and other user research methods must be conducted at regular intervals throughout the development process (not just at the beginning and end) | Artifacts from usability testing and/or other user research methods with end users are available at the end of every applicable sprint, in accordance with the vendor’s research plan | Manual review |

| Organ Matching | Accurate and quick matching between those looking for organs and those that have donated organs. | Upon entering organ information into the system, an answer will be given < 1 minute | Splunk dashboard of matching algorithm logs. |

| System Availability | Modern observability tools (such as a system heartbeat check) are deployed in production. | Organ API uptime to be > 99.99% | DevOps tools such as PagerDuty or AWS CloudWatch are deployed and used in production. |

| System Availability | API response time best practices suggest API response time is under 1 second. | Organ API 95% percentile response time < 500ms | New Relic |

| System Transparency | All organ donation referrals are put on the OPTN donation list through the referring donor hospital. | Donor list contains > than 99% of all possible donors referred from donor hospitals. | Combination of manual review and monthly donor hospital referral reports. |

| System Transparency | OPTN technology must be developed through git source control and managed by the government. | 100% of OPTN code is managed through source control managed by the government. | Automated development and deployment scripts hooked into source control. |

Proposal Submission

Introduction

The Offeror’s proposal shall be submitted electronically by the date and time indicated in the solicitation via email to (insert name of Contact Specialist) at (@.gov) in the files set forth below. The Offeror’s written proposal shall consist of five (5) volumes:

- Volume I: Case Studies (Technical Factor 1)

- Volume II: Written Technical Approach (Technical Factor 3)

- Volume III: Price

- Volume IV: Past performance (Technical Factor 4)

- Volume V: Offer & Award Documents, Certifications & Representations

The Offeror’s proposal will also include a Design Challenge (Technical Factor 2). The use of hyperlinks or embedded attachments in proposals is prohibited except for artifacts.

Proposal Files

Offeror’s responses shall be submitted in accordance with the following instructions:

Format

The submission shall be clearly indexed and logically assembled. Each volume shall be clearly identified and shall begin at the top of a page. All pages of each volume shall be appropriately numbered and identified by the complete company name, date and (when applicable) for each volume of the Offeror’s proposal.

All files will be submitted as either a Microsoft Word (.doc or .docx) or Microsoft Excel (.XLS or .XLSX) file, both of which shall be password protected (the Government shall not be provided the password). Page size shall be no greater than 8 ½”; x 11”; portrait orientation only. The top, bottom, left and right margins shall be a minimum of one inch (1”) each. Font size shall be no smaller than 12-point. Arial or Times New Roman fonts are required. Characters shall be set at no less than normal spacing and 100% scale. Tables and illustrations must be no smaller than 8-point. Line spacing shall be set at no less than single space.

Each paragraph shall be separated by at least one blank line (minimum 6-point line). Page numbers, company logos, and headers and footers may be within the page margins ONLY, and are not bound by the 12-point font requirement. Footnotes to text shall not be used.

All proprietary information shall be clearly and properly marked. If the Offeror submits annexes, documentation, attachments or the like, not specifically required by this solicitation, such will count against the Offeror’s page limitations unless otherwise indicated in the specific volume instructions below. Pages or content in violation of these instructions, either by exceeding the margin, font, printing, or spacing restrictions or by exceeding the total page limit for a particular volume, will not be evaluated. Pages or content not evaluated due to violation of the margin, font or spacing restrictions will not count against the page limitations. The page count will be determined by counting the pages in the order they come up in the print layout view.

Content Requirements

All information shall be confined to the appropriate file. The Offeror shall confine submissions to essential matters, sufficient to define the proposal and provide an adequate basis for evaluation. Offerors are responsible for including sufficient details, in a concise manner, to permit a complete and accurate evaluation of each proposal. Volume 1 Case Studies will be due in accordance with the Due Date included on the RFP’s cover page. Volumes II, III, IV and V will be due after the completion of all Offeror’s Design Challenge and will be due on the same date for all Offerors, which will be provided in each Offeror’s Advisory Letter. The titles and page limits requirements for each file are shown in the Table below:

| Volume Number | Factor | File Name | Page Limitations* |

| Volume I | Case Studies (Technical Factor 1) | Tech1.doc or docx | 6 (not including artifacts, subcontractor list or certification letter) |

| Volume II | Written Technical Approach (Technical Factor 3) | Tech2.doc or docx | 10 |

| Volume III | Price | Price.xls or xlsx | None |

| Volume IV | Past Performance (Technical Factor 4) | PP.doc or docx | 1 |

| Volume V | Offer & Award Documents, Certifications and Representations | OfrRep.pdf | None |

*A Cover Page, Table of Contents and/or a glossary of abbreviations or acronyms will not be included in the page count of Volumes I or II. However, be advised that any and all information contained within any Table of Contents and/or glossary of abbreviations or acronyms submitted with an Offeror’s proposal will not be evaluated by the Government.

Volume 1- Technical Factor 1 - Case Studies

Offerors shall submit up to three relevant case studies for evaluation. Relevant case studies must demonstrate recent (within the past three (3) years immediately prior to the date of solicitation) performance of tasks related to user research and user story collaboration, agile software development, and DevOps, performed by the Offeror or any proposed major subcontractor.

A major subcontractor is one who is anticipated to be meaningfully used during performance of the task order. Accordingly, Offerors shall sign and submit a certification letter (Attachment 003) with their Case Studies that certifies that the proposed major subcontractor(s) are anticipated to provide support during contract performance and that no consultants were used during the preparation of the Case Studies, nor will they be used for preparation of the Technical Factor 3 Written Technical Approach, nor during a Design Challenge.

Case Studies may reflect work completed for Government and/or Commercial clients. Offerors shall provide, in addition to the 3 Case Studies, a list of all Major Subcontractors and which of the three (3) aforementioned Functional Areas they will be meaningfully involved with during contract performance (this list will not count against the nine (9) page count). At least one (1) of the three (3) proposed Case Studies must relate to work conducted by the Prime Contractor which must describe work related to one of the three following areas: user research and user story collaboration, agile software development, and DevOps. Additionally, only one Case Study can be from a Large Contractor (as determined by the Small Business Administration for the designated NAICS code for this procurement).

Offerors must include the following details for each case study submission:

- Client organization name

- Period of performance

- Offeror’s role for the Case Study (e.g. were you the prime contractor or a subcontractor)

- Product or project goals, outcomes, and impact

- Technology Stack (highlighting use of modern or innovative technologies)

- Delivery Methodology

In addition to the above, Offerors are required to submit Artifacts to further demonstrate their capacity to meet the objectives set forth in the Statement of Objectives using user research and user story collaboration, agile software development, and DevOps. Artifacts can take many formats including but not limited to text files, PDF documents, or image files. Artifacts must be related to the work described in one or more case studies. Artifacts may include client deliverables, code, and/or screenshots. Artifacts must not be created in response to this solicitation, they must be work products generated for the described case study, however, the Offeror may transfer original artifacts to a new format for submission. For example, the Offeror may take a screenshot of a webpage or copy site code into a text file. Artifacts may be anonymized as needed to protect Personally Identifiable Information, Personal Health Information, or other proprietary data, but should still demonstrate the vendor’s expertise as it relates to user research and user story collaboration, agile software development, and DevOps as well as validate the past expertise detailed within the Case Study(s). Artifacts may all be from a single Case Study, or from multiple Case Studies, but there must be at least one artifact specifically related to each of the three (3) following relevant Functional Areas (Offerors shall note in their Case Study submission which artifact(s) are intended to meet each of the three (3) functional areas), with a max of nine (9) artifacts total:

-

Agile software development

- Developing software in an iterative style following the modern best practices described in the Digital Services Playbook (https://playbook.cio.gov)

- Developing custom software or configurations in a modern software version control system

-

User research and user story collaboration

- Using a range of qualitative and quantitative user research methods to determine people’s goals, needs, and behaviors

- Documenting user research in a form that HHS/HRSA and other contractors can easily access and learn from

- Working with the product owner or other HHS/HRSA staff to generate and prioritize user stories based on this research

-

DevOps

- Continuous deployment of code to testing, staging, and production instances in a commercial cloud environment

- Automated testing suite integrated into a continuous integration workflow

- Application health monitoring

The Case Studies and their respective artifacts (please include name of case study in the file name along with the name of the respective artifact and do not combine them as each one should stand alone), shall be provided via email to (contract specialist)@___.gov on the due date included in the solicitation. Any explanations related to the artifacts shall be included at the bottom of each case study. On a separate document please submit a list of all major subcontractors regardless of whether they have a case study attributed to them including their DUNS, socio-economic size status, and the Functional Area(s) they are anticipated to support.

Technical Factor 2 - Design Challenge

The Design Challenge will be conducted either in person or remotely. The remote option will use a series of Zoom or Google Meet account meetings hosted by the Government. The exact date, time, and a meeting link will be provided in the advisory notification provided after the evaluation of the Case Studies. The Government will schedule the Design Challenge by drawing lots among those Offerors who elect to proceed after the Technical Factor 1 advisory down-select. The Government will advise Offerors of the date and time of their Design Challenge which is anticipated to be held between (Month Day, Year) and (Month Day, Year). Only employees of the Prime Contractor or a proposed Major Subcontractor (as defined above and as listed in the Case Study Volume) may participate in the Design Challenge.

The goal of the Design Challenge is to evaluate the Offerors’ ability to solve problems using their agile software development approach. Specifically, the Design Challenge will be an opportunity for vendors to demonstrate their abilities in problem definition, user research, development of agile epics/stories, Minimally Viable Product selection, and design iteration/prototyping. Offerors will complete a design sprint including in person or remote agile ceremonies with the Government. Offerors will be given a scenario detailing a fictional government problem and will have six (6) business days to complete the sprint. The following schedule provides the timing of the events during this sprint:

Business Day 1: Scenario and Test

The Offeror will join a 15-minute Zoom call to test the technology, during this meeting the Offeror will be emailed, and will then confirm receipt of, the email containing the fictional scenario. This confirmation will constitute the official start time for the Design Challenge. The Offeror will prepare for the Sprint kick-off planning ceremony the following day. Additionally, Offerors will provide the full list of all participants for their Design Challenge, including whether they are from the Prime Offeror or from a Major Subcontractor. Only participants identified on the call may participate in the Design Challenge. This will not be an evaluated step.

Business Day 2: Sprint Planning

The Offeror will join a 1-hour Zoom call and conduct Sprint Planning. The Government will provide an actor during this meeting to play the role of the Product Owner for the fictional scenario. During the meeting the Product Owner will be available to answer questions, confirm or refute assumptions, and provide feedback on epics/stories. The Product Owner will be available to the Offeror only during this 1-hour meeting. Following Sprint Planning, the Offeror will carry out the agreed to plan until the Sprint Demonstration and Team Retrospective.

Business Day 6: Sprint Demonstration and Team Retrospective (Retro)

The Offeror will join a 2-hour Zoom or Google Meet call and conduct a Sprint Demonstration and Team Retrospective. The Sprint Demonstration will be the first 45 minutes of the meeting. During the Sprint Demonstration, the Offeror will provide a status update including planned epic/story points, completed epic/story points, and notes. The Offeror will demonstrate the epics/stories completed during the sprint. The following 30 minutes will be the Sprint Retrospective (Retro). During the Sprint Retro, the Offeror will collect and discuss feedback from their team about the Sprint. After the completion of the Retro, the Government will take a 15-minute break to discuss the Offeror’s Retro and determine if it has any questions, while leaving the Zoom or Google Meet meeting active and muted. The final 30 minutes of the meeting will be dedicated to Government Question and Answer (Q&A), if any, with the Offeror. These Question and Answer exchanges do not count as discussions.

The Design Challenge is an opportunity for the team to demonstrate the Digital Services including cross-team collaboration, agile methods, user-centered design, and iterative development needed to accomplish the objectives in the Statements of Objectives.

All supporting digital (including any code developed during the Design Challenge, photos, and screenshots) and non-digital artifacts created during the Design Challenge shall be submitted at the end of the Design Challenge; video files will not be accepted. The submission shall be via a private GitHub repository the link to which shall be emailed to (contract specialist@__.gov at the completion of the Design Challenge. The Offeror shall provide the Government GitHub Account [CATCHY PROCUREMENT NAME-Evaluator] access to the private repository. Images of non-digital artifacts created during the Design Challenge can be uploaded to the GitHub repo. These artifacts shall be representative of the Offeror’s proposed process for documenting work. The Government’s confirmation of receipt of the Offeror’s email will constitute the official end of the Offeror’s Design Challenge. Nothing shall have been configured or committed to the GitHub repository provided at the end of the Design Challenge prior to the official start time of the Design Challenge as confirmed by the Government during the Scenario and Test meeting.

PLEASE NOTE: Although major subcontractors are free to partner with more than one prime Offeror, for the Design Challenge, individuals who support one Design Challenge (whether employees of the prime or a subcontractor) must be used on only one prime Offeror’s Design Challenge Team. Accordingly, should there be an individual who supports one prime Offeror’s team that arrives for a second Design Challenge for a different prime Offeror, the Government reserves the right to remove both prime Offerors from further consideration for award. Additionally, all Offerors shall sign and submit the Certification Letter for Design Challenge (Section ** , Attachment ** ) prior to the start of the Design Challenge confirming that there will be no overlap between Design Challenge teams who share a common subcontractor, nor will there be any communication between the two teams at any point during the Design Challenge process. Further, prior to the start of the first 15-minute “Scenario and Test” Zoom (or Google Meet) call to the Design Challenge, all participants will be asked to sign and return the Non-Disclosure Agreement which is set forth in Section ** , Attachment ** of the solicitation at the same time Attachment ___ is submitted.

Volume II - Technical Factor 3 - Written Technical Approach

The Written Technical Approach shall be limited to 10 pages, excluding the cover letter and table of contents, and list of acronyms. Within the Written Technical Approach, the Offeror shall provide a detailed approach to the following:

- How does your organization recruit, hire, and retain talented individuals in the fields of product management, research and design, and software engineering?

- How does your organization ensure the delivery of quality and consistent design products and functional code?

- How does your organization foster effective teamwork during agile service delivery?

- How does your organization collaborate in work environments that involve multiple Government stakeholders and external contractor teams?

Volume III - Price

The Offeror is required to complete and submit the Government provided “Price Evaluation Spreadsheet” found as Attachment ___. Instructions for the Spreadsheet can be found in the Worksheet entitled “Instructions.” The Offeror shall input a fully loaded blended labor rate for each labor category that will be valid for the Prime and its subcontractors, as well as a handling rate for Materials and Travel that will become binding ceiling rates for any resultant contract.

Fully loaded labor rates proposed shall be two decimal places.

Volume IV - Past Performance

The Offeror is required to submit past performance in organ procurement and transplantation. Note that Offerors who have no relevant Past Performance will receive a neutral score for Technical Factor 4.

Volume V - Solicitation, Offer & Award Documents, Certifications & Representations

(fill in with appropriate documents related to solicitation, offer and award documents, and certifications and representations)

Offerors are hereby advised that any Offeror-imposed terms and conditions and/or assumptions which deviate from the Government’s material terms and conditions established by the Solicitation, may render the Offeror’s proposal Unacceptable, and thus ineligible for award.

Basis for Award

The source selection process for (Catchy Procurement Name) will neither be based on a Lowest Price Technically Acceptable basis nor Tradeoffs. For this effort, the Highest Rated Offerors with a Fair and Reasonable Price will determine the best value basis for the award of contracts under this solicitation.

As there will be no tradeoff between any of the four (4) Technical Factors and Price, there is no relative weighting between the non-Price Factors and the Price Factor. This is because the methodology will evaluate pricing of only those Offerors which achieve the highest technical ratings.

The Government intends to award one task order resulting from the (Catchy Procurement Name) solicitation to one (1) Offeror; however, the Government retains the right to award more than one (1) award should it be determined in its best interest. In the event the Government does decide to award more than one (1) task order resulting from this solicitation, it will award the task order to the next highest ranked Offeror(s). If one (or more) of the Offerors in the top verified ratings (should the Government make additional awards) is found to not have a fair and reasonable price, it will be eliminated from the ranking. No further ranking beyond the awardees will be made.

Any award will be made based on the best overall (i.e., best value) proposals that are determined to be the most beneficial to the Government, with appropriate consideration given to the five following evaluation Factors: Technical Factor 1—Case Studies, Technical Factor 2—Design Challenge, Technical Factor 3—Written Technical Approach, and Price.

Technical Factor 2 is slightly more important than Technical Factor 1, which is significantly more important than Technical Factor 3. Technical Factor 4—Past Performance is far less important than any other Technical Factor (Note that Offerors who have no relevant Past Performance will receive a neutral score for Technical Factor 4). As there will be no tradeoff between any of the four (4) Technical Factors and Price, there is no relative weighting between the non-Price Factors and the Price Factor. To receive consideration for award, a rating of no less than “Acceptable” must be achieved for Technical Factors 2 and 3 and the Offeror’s Price must be determined Fair and Reasonable. This methodology considers the non-price factors, when combined, to be significantly more important than price.

FACTORS TO BE EVALUATED

- TECHNICAL FACTOR 1— CASE STUDIES

- TECHNICAL FACTOR 2— DESIGN CHALLENGE

- TECHNICAL FACTOR 3— WRITTEN TECHNICAL APPROACH

- TECHNICAL FACTOR 4— PAST PERFORMANCE

- PRICE

EVALUATION APPROACH

All proposals shall be subject to evaluation by a team of Government personnel. The Government reserves the right to award without discussions based upon the initial evaluation of proposals. If discussions are entered, they will only be for Technical Factor 3, Price, and/or the Solicitation, Offer; Award Documents, Certification and Representations Volumes as applicable; Offerors are advised they will not be permitted to revise their submitted responses for either Technical Factor 1, Technical Factor 2, or Technical Factor 4 in the event discussions are opened. The proposal will be evaluated strictly in accordance with its written and/or demonstrated content. Proposals which merely restate the requirement or state that the requirement will be met, without providing supporting rationale, are not sufficient. Offerors who fail to meet the minimum requirements of the solicitation in Technical Factors 2 and 3 will be rated Unacceptable and thus, ineligible for award. Offerors who have no relevant Past Performance will receive a neutral score for Technical Factor 4.

TECHNICAL EVALUATION APPROACH

The evaluation process will consider the following:

-

TECHNICAL FACTOR 1 - CASE STUDIES

Technical Factor 1 shall evaluate the Government’s confidence in the Offeror’s ability, as evidenced by the past experience and expertise identified within each Case Study, as well as all artifacts provided with the Case Studies, to accomplish the objectives set forth in the Statements of Objectives. Although there is no specific rubric for evaluation of Case Studies, the provided artifacts will be evaluated based on how well they align with the narrative description provided for their respective case study, the technical quality of the artifact, and the appropriateness of the artifact to the functional area to which it is being proposed.

After the Government completes evaluation of the Technical Factor 1-Case Studies, the highest rated Offerors will receive an advisory notification advising them to proceed to Technical Factors 2 and 3. Lower rated Offerors will be advised they are unlikely to be viable competitors. The intent of this advice is to minimize proposal development costs for those Offerors with little chance of receiving an award. However, the Government’s advice will be a recommendation only, and those Offerors may elect to continue their participation in the acquisition. All Offerors who elect to continue their participation shall provide notification no later than 5PM ET the next business day to HHS/HRSA after which they will be provided the dates and times for the Design Challenge and the due dates for the Written Technical Approach, Price, Offer & Award Documents, Certifications & Representations Volumes.

- TECHNICAL FACTOR 2 – DESIGN CHALLENGE AND

-

TECHNICAL FACTOR 3 - WRITTEN

TECHNICAL APPROACH: The evaluation of Technical Factor 2-Design Challenge and Technical Factor 3-Written Technical Approach will consider the following:

- Understanding of the Problem – Technical Factor 2 and Technical Factor 3 will be evaluated to determine the extent to which the Offeror’s approach demonstrates a clear understanding of all features involved in solving the problems and meeting and/or exceeding the requirements presented in the solicitation and the extent to which uncertainties are identified and resolutions proposed.

- Feasibility of Approach – Technical Factor 2 and Technical Factor 3 will be evaluated to determine the extent to which the proposed approach is workable and the end results achievable. They will be evaluated to determine the level of confidence provided the Government with respect to the Offeror’s methods and approach in successfully meeting and/or exceeding the requirements in a timely manner.

-

TECHNICAL FACTOR 4 – PAST PERFORMANCE

The evaluation of Technical Factor 4-Past Performance will consider the information obtained from the awards and references provided in the offeror’s responses to the RFP, information from www.cpars.gov, information from other customers known to the Government, and other sources who may have useful and relevant information. Evaluation of past performance may be quite subjective, based on consideration of all relevant facts and circumstances. Note that Offerors who have no relevant Past Performance will receive a neutral score for Technical Factor 4.

PRICE/COST EVALUATION APPROACH

This evaluation will not result in a Total Evaluated Price. Proposed prices, including all proposed fully burdened Labor Rates, Material Handling Rate, and Travel Handling Rate, will only be evaluated to determine that the proposed Rates are fair and reasonable. Additionally, only Offerors determined to be the highest technically ranked will have their price proposals evaluated. The fair and reasonable evaluation of rates will be used to establish Maximum Rates on awarded call orders. Such Maximum Rates will apply to Firm-Fixed-Price (FFP) orders and Time-and-Material/Labor-Hour orders, however, on FFP orders Offerors may propose other Labor Categories when that labor rate is not on contract. Additionally, Offerors shall propose a handling rate to be applied to Materials and Travel which will be incorporated into any resultant contract as a ceiling rate.

For each proposed fully burdened direct labor rate, the basis for the proposed maximum fair and reasonable rates (Attachment 001, column I), used as the basis for comparison, will be labor rates found in the GSA CALC Tool for the Labor Categories included in the attachment. Failure to provide a rate for each listed Labor Category in Attachment 001 may render the Offeror’s price proposal inadequate and preclude the Offeror from further consideration for award. The Government has established Interquartile Ranges based on the labor rates found in the GSA CALC Tool and then applied the Tukey Rule to establish the maximum rates used as the basis for comparison and included in Attachment 001. The proposed fully burdened Labor Rate for each Labor Category listed in the Price Evaluation Spreadsheet, Attachment 001, will be compared to the “maximum fair and reasonable labor rate” listed in column I of Attachment 001. to ensure it does not exceed the maximum rate. As long as all rates are at or lower than the maximum rate for each Labor Category, the proposed rates will be determined fair and reasonable. Should a single proposed rate exceed the listed maximum rate in any Labor Category, the Government reserves the right to determine the Offeror’s entire Price Proposal to be not fair and reasonable and remove the Offeror from further consideration for award.

Notes

Requirements Document

Background

A requirements document is a necessary part of a Request for Proposal (RFP). It describes the need. In this case, the need is for modern technology that supports organ donation reform. There are different forms of requirements documents, from less to more prescriptive about what is to be built or delivered under contract. When it comes to buying technology, a government team who is less mature in digital services should especially default to less prescriptive while a more mature team will likely prescribe how the government wants the vendor to work.

A Statements of Objectives (SOO) provides basic, high level objectives of the acquisition and is the least prescriptive choice of a requirements document. It allows industry to re-imagine innovative approaches to achieving the objectives. The SOO opens up the acquisition to a wider range of potential solutions. While the SOO is included in the RFP, it will not be a part of the eventual contract. When vendors submit proposals in response to the RFP, they submit a technical approach in the form of a Statement of Work (SOW) which clearly describes the performance objectives and standards that are expected of the vendor.

Statements of Objectives

Product Vision

For donor hospital and transplant center clinicians, organ procurement organizations, researchers and health agencies who need to efficiently and clinically match donor organs with transplant candidate recipients across the nation, and to make continuous improvements to that system the ModernOrganSystem is a matching technology that tracks donor hospital referrals, house recipient candidate information (waitlist), matches organs using clinical algorithms, and logs all transplant outcomes unlike DonorNet our product increases transplants in the US and reduces mortality and costs.

Objectives

The major objectives to be accomplished include:

- To capture all relevant data necessary to support the goals and objectives of the OPTN

- Develop and implement in production organ matching algorithms based on clinical best practices and objective metrics put forth by the OPTN committee

- Develop applications to support fulfill OPTN key performance indicators such as that ‘no organs are lost in transit’

- Efficiently matching available organs with recipients through an automated process

- Develop OPTN applications that support equitable allocation of organs regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, pediatrics, and those with increased risk or existing conditions

- OPTN development adheres to a scrum process of incremental product development driven by human centered research

- To provide one source of truth for data, owned and accessible by the government, for all of organ transplant

- Provide necessary organ related data through protected API access that meet minimum SLA standards defined in the QASP

- To push or allow data access in real time (push data via open API in real time, e.g., to SRTR, HHS, or another third party)

- To capture a log of all referrals from donor hospitals, even those who do not become donors

- To minimize account user behavioral bias

- Follow product development methodologies that use human centered design to ensure organ and OPTN applications are designed with end users and for them

- To drive the organ donation field forward and help researchers and clinicians build or see insights