Summary of Findings

Each year, more than 28,000 viable organs are wasted. Despite scientific advancements, the organ donation system is held back by poor management and performance. The U.S. government could save tens of thousands of lives and billions of dollars by holding contractors to more rigorous standards and modernizing the technology within the organ transplant ecosystem.

When people hear “organ donation,” they might only think about a box they checked off when renewing their driver’s license. While checking that box can be a helpful first step to saving lives through organ donation, most people don’t realize that there is a huge ecosystem behind what makes organ transplants happen — or not happen. People might assume because organ donation is so important, the system must be well-run. But in reality, it’s not. In fact, Americans are unnecessarily losing thousands of lives and billions of taxpayer dollars each year from what’s broken in this system.

The Effects of a Broken System

Today, the medical community continues to make advancements in the field of organ donation and transplantation. Yet this life-saving science relies on an outdated system that has failed to scale up to modern day management and technology best practices.

How does this system hurt Americans? Imagine you need an organ and manage to join the 109,0001 people on the waiting list – which in itself can be a challenge.2 Once you’re over the hurdle of getting on the list, you have only a 50% chance of receiving the organ you need within the next 5 years.3

The problem is even worse for people of color,4 who are less likely to get on the waitlist5 and less likely to find a match once they’re on there.6 Black families are also less likely to even be asked about donation – and face lower quality interactions when they are approached7 – which contributes to the low match probability for Black patients.8

One might think with all the people on the waitlist, and with 90%9 of Americans supporting organ donation, that nearly all viable organs from deceased donors will get used. But disturbingly, that’s not the case. Less than half of people in the U.S. who meet established criteria for organ donation actually become donors.10

That means around 28,000 life-saving organs every year, on average, are not transplanted.11

Additionally, taxpayers could save $40 billion in 10 years if more organs were recovered, according to research.12 Without a transplant, patients with kidney failure have to rely on costly and painful dialysis. Medicare currently spends $36 billion13 every year on dialysis and treatment for people with End Stage Renal Disease – which is more than the annual budget for NASA14 and the CDC15 combined.16

“[A]n astounding lack of accountability and oversight in the nation’s creaking, monopolistic organ transplant system is allowing hundreds of thousands of potential organ donations to fall through the cracks.”

- New York Times Editorial Board

Key Findings and Opportunities

After speaking with organ procurement organization (OPO) leaders, transplant centers, government officials, and other organ donation experts, our findings reveal a number of critical issues with how the organ transplant system has been built and continues to run. There are several root causes that illustrate the need for change.

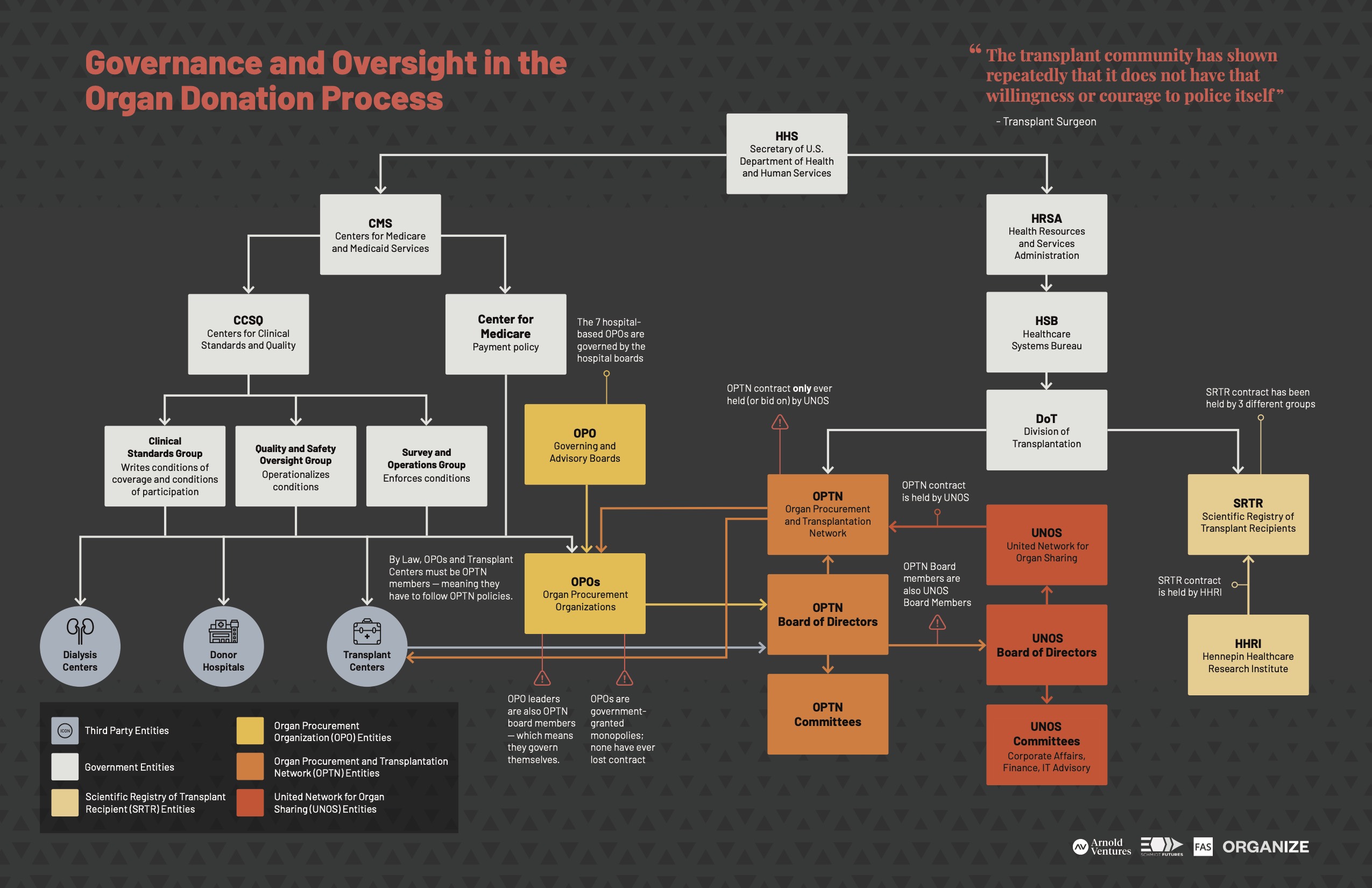

A convoluted governance structure leads to problematic oversight

Responsibilities around organ donation and transplantation in the U.S. are diffused across several different government agencies and contractors (see “Governance and Oversight in the Organ Donation Process,” Figure 1), leading to an unnecessarily complex — and conflicted — structure.

Figure 1

Download the “Governance and Oversight in the Organ Donation Process” PDF

“It’s a perfect complexity; everyone is focused on their own problem, and ignoring the rot underneath.”

- Senior Government Official

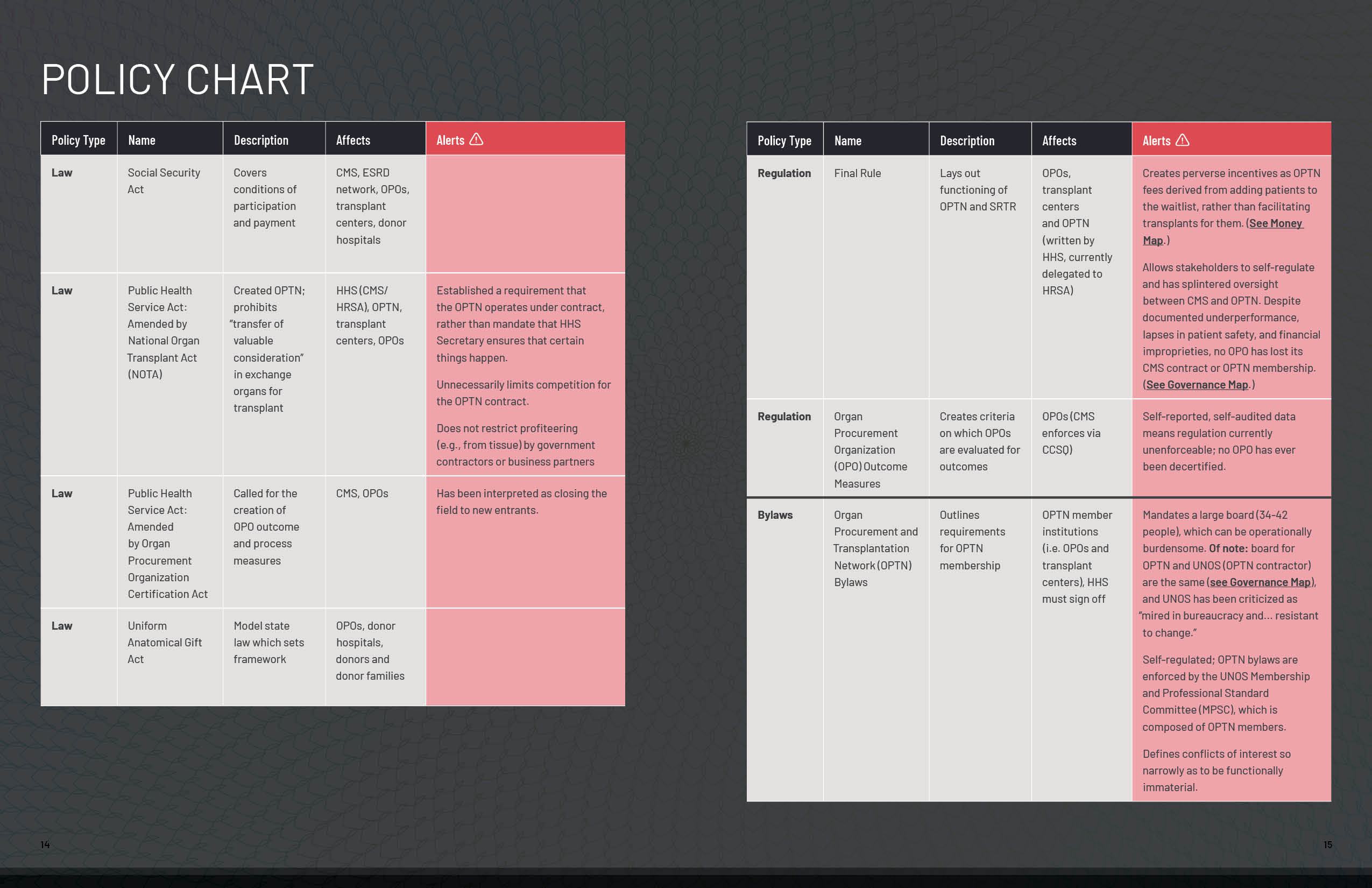

When Congress passed the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) of 1984, the government established the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and mandated that it be operated by a private contractor. The contract is currently overseen by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) under Health and Human Services (HHS). The only contractor who has ever held the contract is the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). (See “Organ Donation Policy,” Figure 2.)

Figure 2

Download the “Organ Donation Policy Chart” PDF

While HRSA is responsible for the regulation and oversight of the OPTN, another HHS agency, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), is stuck footing the bill. Government contractors who coordinate organ recovery, known as organ procurement organizations (OPOs), are 100% reimbursed for all expenses, and OPOs’ failure to recover enough kidneys contributes to billions each year in taxpayer dialysis costs. CMS and the OPTN are also both responsible for overseeing OPOs, which we discuss more below.

Rather than working together to solve problems that arise, the existing governance structure enables each arm to pass accountability back and forth, resulting in issues falling through the cracks. As one interviewee explained, HRSA and CMS tend to pin problems on each other, and rely on the OPTN contractor, instead of working together to create a cross-HHS solution.

“There’s a sensitivity to addressing the controversies because then HRSA has to admit that there was a problem there in the first place that they allowed [or] didn’t fix. So they point instead to some other problem. It’s a conflict-avoidance strategy.”

- Senior Government Official

The HRSA team assigned to oversee the OPTN contract is roughly 3 1/2 employees. Since the OPTN is responsible for the technology that connects the organ transplant ecosystem as well as overseeing the country’s 58 OPOs, it is concerning that only 3 1/2 employees are tasked with effectively overseeing this massive responsibility.

Little accountability contributes to poor performance

OPOs play the vital role of procuring organs, finding a matching recipient, and delivering those organs to transplant centers for the actual procedure. Each of the 58 OPOs in the U.S. operate without competition from any other organizations in their respective regions, effectively making them monopolies. In addition, there is no standard way that OPOs operate. This leads to a wide variance of performance — up to a 470% difference between the best and worst OPOs in terms of potential organs recovered.17

“The greatest gap between where we are and where we wanted to be could be covered by having every OPO operate as effectively as the most effective OPOs.”

- Former White House Senior Advisor

A recent CMS proposed rule has shown that a majority of OPOs are failing basic proposed outcome metrics,18 resulting in many organs going unrecovered, mishandled, or even lost. (See “The Most Frequent Causes of Wasted Organs”)

“We’ve been using the WRONG data and keep missing the problem: too often gov-granted monopoly contractors - called organ procurement organizations (OPOs) - aren’t showing up to honor potential organ donors’ wishes. Literally not showing up.”19

- Former U.S. Chief Data Scientist

Despite massive underperformance, no OPO has lost its government contract in the nearly 40 years the system has operated.

Even though OPOs are technically overseen by the OPTN and CMS, they largely act unchecked, providing unverified, self-reported data.

“There is no provision for even random audits of the data submitted by OPOs to assess the accuracy of the data reporting. All data are self-reported and unverified.”20

- Association of Organ Procurement Organizations

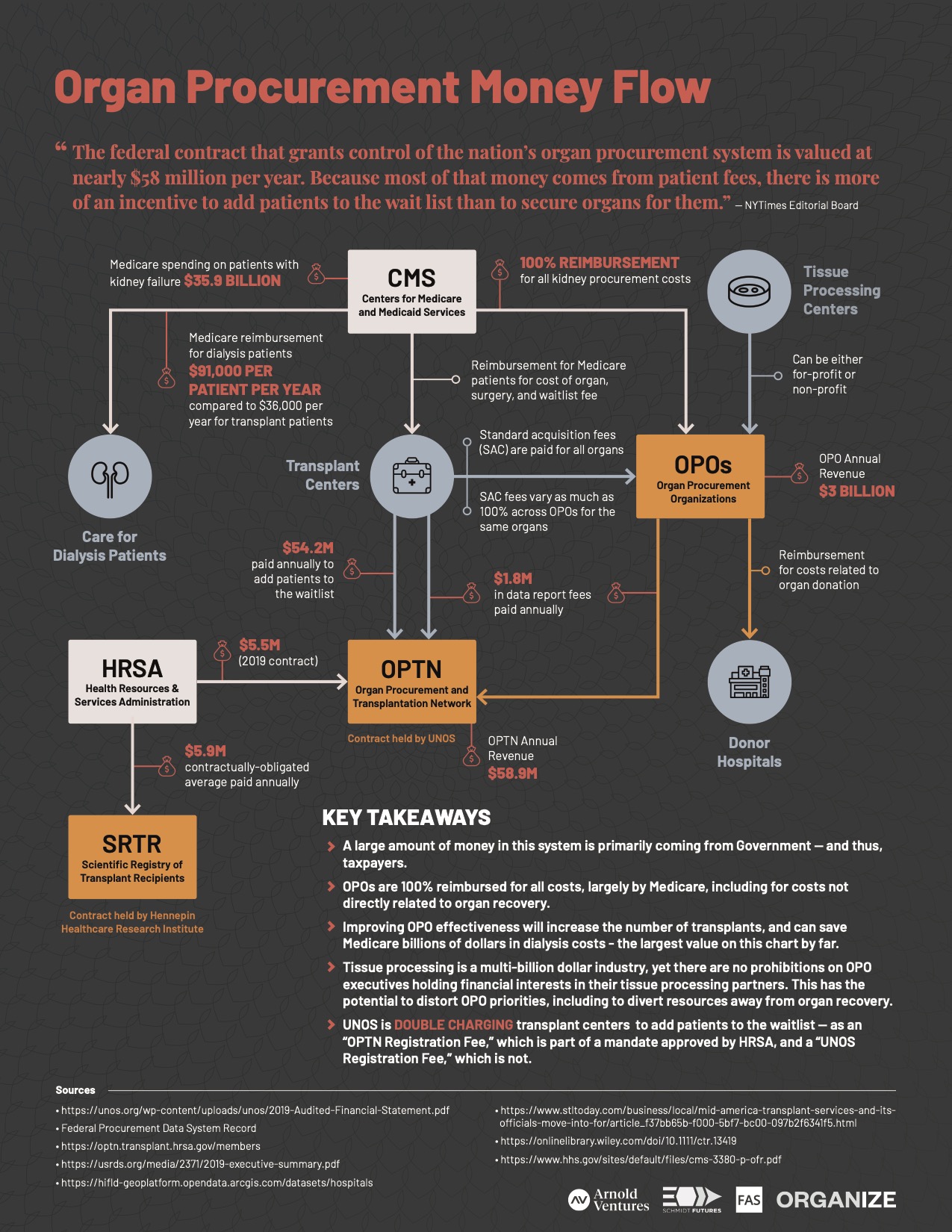

Misaligned incentives lead to fewer recovered organs

The current flow of money and costs (see “Organ Procurement Money Flow,” Figure 3) between agencies and federal contractors overseeing organ procurement and placement does not incentivize getting patients transplants.

Figure 3

Download the “Organ Procurement Money Flow” PDF

The federal contractor in charge of overseeing the U.S. organ procurement system, UNOS, earns about $58 million a year, with the bulk of their revenue coming from transplant centers paying to add patients to the organ waitlist.

“Because most of that money comes from patient fees, there is more of an incentive to add patients to the waitlist than to secure organs for them.”21

- New York Times Editorial Board

UNOS has held the contractor position exclusively since 1986. Since that time, the waitlist has grown considerably.

The current system also does not incentivize OPOs to pursue all donation opportunities. For example, OPOs may deprioritize “low-yield” candidates, for lack of either financial or regulatory pressures to recover and place all transplantable organs. This can result in them rejecting, or simply not showing up for, older donors with only single organs available22 — even though those single organs could each save a life.

While not all patient referrals are clinically able to become donors, a study commissioned by HRSA suggests OPOs are only recovering an estimated “one-fifth of true [donor] potential.”23

The Most Frequent Causes of Wasted Organs:

-

Not all potential donor referrals are made. A referral for a potential donor kicks off the whole organ donation process.24 Organ procurement organizations (OPOs) could work more effectively with donor hospitals to ensure all viable patients are referred. Some researchers, however, say OPOs avoid this to make their numbers look better. “Many OPOs have instructed hospitals to NOT call on certain patients thus eliminating organ donors before they even get to the OPO.” - OPO Leader

-

OPOs fail to show up or decide not to pursue an organ. Researchers suggest this may happen if an OPO coordinator takes too long to get to the hospital, the coordinator or hospital thought the family was unlikely to donate, or it was deemed too highly emotional of a case, among other reasons. Too often, this involves bias against patients of color.25 “Where OPOs ‘determine’ eligibility is a HUGE gap in the system. Many OPOs rule out patients that could be ruled in. Lack of training/knowledge, preconceived notions, pure laziness.” - OPO COO

-

OPOs fail to obtain family authorization. Many families report they would have donated if they had been approached correctly. However, poor interactions and poor training contribute to low authorization rates. ”Training keeps getting worse and worse…there’s no standard training, it’s very subjective…. They’re setting [OPO staff] free before they’re really ready.” - OPO Coordinator

-

OPOs do not place organs or get them where they need to be in time. Once an organ is recovered, OPOs rely on an inefficient matching technology from UNOS to place the organ while it is still viable. The algorithm can waste time by suggesting the wrong offers. For example, 17% of kidney offers go to deceased patients.26 “What tends to happen is that sick people get offers for organs that they can’t tolerate because they’re too sick already. They’ll have too many complications. There IS a patient for that organ, but an offer never makes it to a patient who can accept the organ.” - Researcher

Figure 4

Download the “How an Organ is Managed (Or Not) in the Current Organ Donation System” PDF

Core technology and software inhibits innovation and organ policy implementation

Many users we talked to stated that UNOS organ transplant technology felt dated and had frequent periods of downtime, or the system was extremely slow, where they had to rely on phone calls.

Further, the agency tasked with overseeing OPTN/UNOS has few tech staff to effectively audit or implement technical best practices. “We don’t have the in-depth IT staff to have an understanding [of] whether the things [that] are being built are good,” said one HHS official.

Another issue is the number of disparate software systems within the organ transplant tech community. Various contractors each handle their own system and data. This approach prevents a single overseer, like the OPTN, from collecting centralized data and making smarter, data-driven management decisions.

Most software used by UNOS is considered closed and proprietary, blocking any chance of innovation or competition from outside actors. This strongly goes against modern day best tech practices. (See “Tech Recommendations.”) And it has caused the organ donation system to miss the mark on moving the technology forward, blocking out a market of innovative technology options to tackle solvable problems.

A leading healthcare technology executive described the incumbent’s technology inner workings as “literally duct tape.”

With the current technology as an inhibitor, trying to implement a new policy can take over a year – resulting in lives lost and billions of dollars wasted.

The government’s current approach to contracting blocks progress

The government (HHS/HRSA) is extremely limited in its ability to select which vendors can be awarded the OPTN contract, due to overly prescriptive specifications within NOTA. Thus the same vendor, UNOS, has been awarded the contract during every recompete for the past 34 years. These constraints limit progress in developing digital products and services with modern best practices to truly support the system. (See “Strategy for Buying OPTN Tech.”)

Additionally, as mentioned above, in the past 40 years, none of the OPOs in the U.S. have lost their federally-funded positions, despite clear evidence of underperformance.27

Where Do We Go From Here?

The good news is that many of these problems are solvable. We believe it is within reach to create a system that is less complicated and saves more lives and taxpayer dollars in the short and long term.

Below are key opportunity areas to increase the effectiveness of the organ transplant system.

Opportunities to modernize and remove conflicts from governance structure:

- Broaden options for HHS to more freely fulfill organ donation objectives without needing to designate as many functions to a contractor, and maximize competition for work done by the OPTN, so that HHS can access a much larger vendor pool.

- Centralize governance and oversight to contractors working on organ donation within one department, and staff it with a digital service team that can adequately manage and run technology services.

- Use modern acquisition strategies for technologies related to the OPTN. (See Strategy for Buying OPTN Tech.)

Opportunities for CMS to improve accountability in organ recovery and placement:

- Require objective, verifiable, and real-time data from OPOs on the number and timeliness of staff follow-up for all eligible donors, and whether follow-up was onsite.

- Increase training quality for OPO staff requesting authorization from families of donors to include communication best practices, implicit bias, and trauma-informed care.

- Include standardized protocols for hospitals on identifying and referring potential donors — both donation after brain death (DBD) and donation after cardiac death (DCD) cases.

Opportunities for improved technology in organ donation:

- Ensure future OPTN contractors use open-source, cloud-based technology. Open-source is essential so the government has flexibility to access and refresh all parts of the technology stack.

- Create or require a central data warehouse that enables data-driven decision making and more transparent public-facing data, with standardized metrics.

- Improve organ offer technology to ensure all organs find a suitable recipient. This improved technology should ensure no offers go to deceased patients. It could also include assisted clinical decision making28 to help transplant centers quickly decide whether to accept.

Medical professionals save nearly 100 lives every day with organ transplants.29 People currently waiting for a heart, lung, kidney, liver, or pancreas face the painful reality that the science exists to save them, and yet it’s an outdated, bureaucratic system that’s getting in the way. Employing a few structural changes could have a massive impact on the number of lives saved.

Methodology

Researchers, including former government experts, interviewed more than 30 people within the organ donation system, including OPO leaders and staff, organ specialist consultants, donor hospital staff, transplant surgeons, government officials, and researchers. This report is based on those interviews, case studies, and existing research, as well as the OPO Best Practices and Tech Recommendations reports compiled by our researchers.

Research was supported by Arnold Ventures and Schmidt Futures in partnership with Organize and the Federation of American Scientists.

Additional Information

- Download Summary of Findings (PDF)

- Inequity in Organ Donation

- OPO Best Practices

- Technology Recommendations

- Strategy for Buying OPTN Tech

- About the Project

- Appendix

Notes

-

“Donation and Transplantation Statistics,” Donate Life America, 2019. ↩

-

“The Terrible Toll of the Kidney Shortage,” JASN, 2018. ↩

-

“Waiting for Your Transplant,” UNOS, 2020. ↩

-

There are fewer POC donors because of several factors, including: historical mistrust of the healthcare system, and POCs being less likely to be approached by Organ procurement organizations (OPOs), and more likely to receive a lower quality interaction from the OPO when they do get approached to be a donor referral. “More donations are needed from every race… Hispanics, the nation’s largest minority, had a donation rate of 27.5 per million in 2017. And just 15.1 per million Asian-Americans are organ donors. “How a surgeon helped solve the problem of far too few black organ donors,” 2018. ↩

-

“Impact of Race on Predialysis Discussions and Kidney Transplant Preemptive Wait-Listing,” American Journal of Nephrology, 2012. ↩

-

”Organ Donation and African Americans,” HHS, 2020. ↩

-

”Comparison of black and white families’ experiences and perceptions regarding organ donation requests,” Critical Care Medicine, 2003. ↩

-

“Although organs are not matched according to race/ethnicity, and people of different races frequently match one another, all individuals waiting for an organ transplant will have a better chance of receiving one if there are large numbers of donors from their racial/ethnic background. This is because compatible blood types and tissue markers—critical qualities for donor/recipient matching—are more likely to be found among members of the same ethnicity,” Race And Organ Donation, Gift of Life Donor Program. ↩

-

”Organ Donation Statistics,” HRSA, 2020. ↩

-

”Lives Lost, Organs Wasted,” Washington Post, 2018. ↩

-

“Reforming Organ Donation in America,” Bridgespan, 2019. Updated projections, Bridgespan, 2020. ↩

-

“A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Government Compensation of Kidney Donors,” NCBI, 2015. ↩

-

“Do kidney transplants save money? A study using a before-after design and multiple register-based data from Sweden,” NCBI, 2017. ↩

-

“Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Organ Procurement Organizations Conditions for Coverage: Revisions to the Outcome Measure Requirements for Organ Procurement Organization,” CMS NPRM, 2019. ↩

-

Ibid. ↩

-

DJ Patil (@dpatil), Twitter, July 9, 2019. ↩

-

Letter to Office of Management and Budget from New York Organ Donor Network, 2013. ↩

-

“She Beat Cancer. Now She’s in Another Fight for Her Life,” New York Times, 2019. ↩

-

Letter to Office of Management and Budget from New York Organ Donor Network, 2013. ↩

-

“OPTN Deceased Donor Potential Study,”UNOS, 2015. ↩

-

These typically come from donor hospital staff, or in very limited instances, through an electronic automated system. ↩

-

“Comparison of black and white families’ experiences and perceptions regarding organ donation requests,” Crit Care Med, 2003. ↩

-

”Kidney transplant offers to deceased candidates,” AM J Transplant, 2018. ↩

-

See bipartisan oversight from the Senate Finance Committee, February 2020. ↩

-

”Increasing Kidney Transplant,” Core77, 2020. ↩

-

“Transplant Trends,” UNOS, 2019. ↩