Oversight Gaps and Conflicts

Executive Summary

Every day in the U.S., 33 people die because they don’t have access to an organ transplant, and yet the nation’s organ donation system is leaving behind tens of thousands of viable organs.

Organ donation reform is more urgent now than ever before, given evidence that COVID-19 increases the risk of organ failure. Failures within the U.S. organ donation and transplantation system – which disproportionately harm patients of color – are left unaddressed by oversight bodies. This report examines the current oversight structure and provides recommendations to save more lives through organ donation.

“Failures within the U.S. organ donation and transplantation system – which disproportionately harm patients of color – are left unaddressed by oversight bodies.”

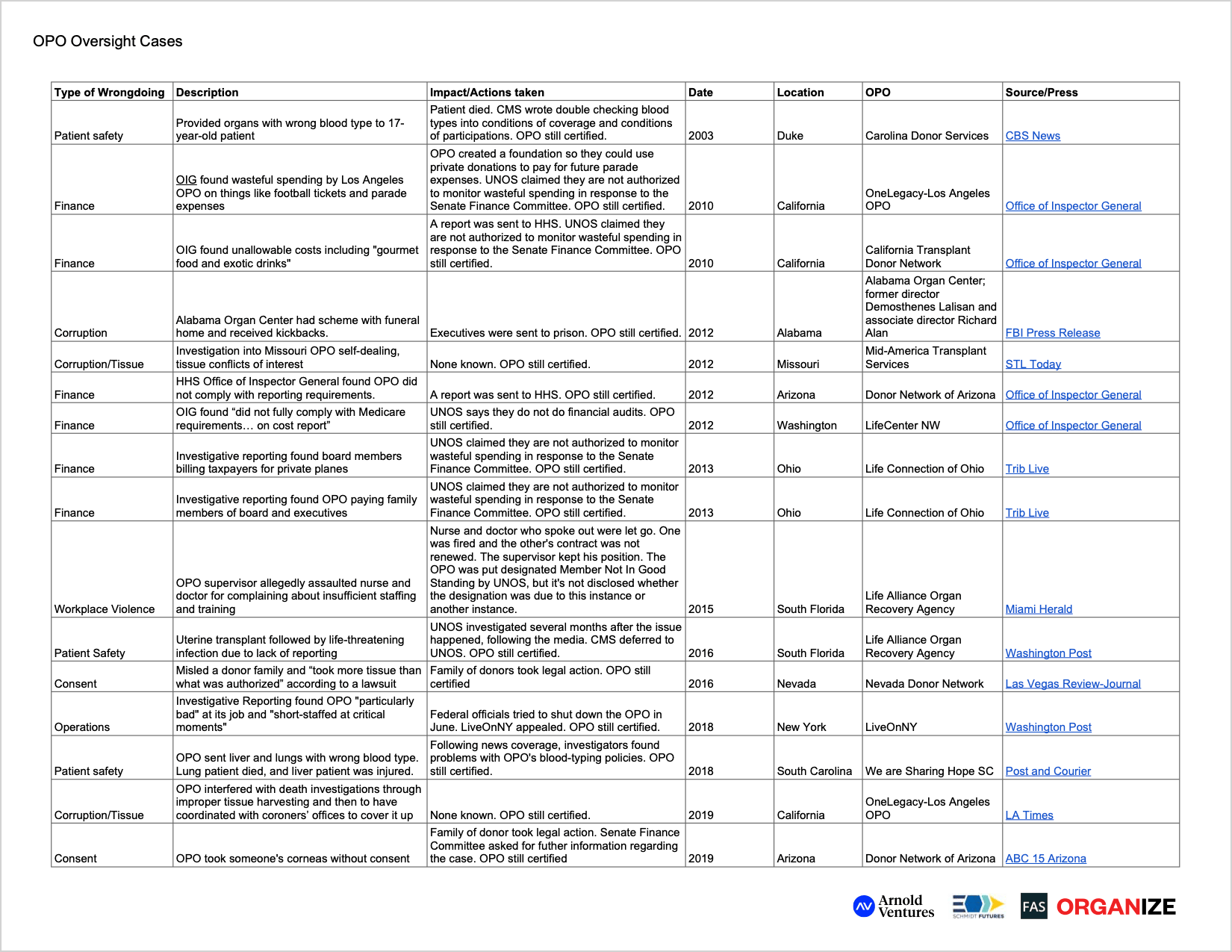

None of the 57 Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs) operating in the U.S. have ever been successfully decertified by the federal government, even OPOs with:

- a 1 in 4 recovery rate of potential donors;

- leaders who went to federal prison for a tissue procurement kickback scheme;

- a failure to report a fungus that nearly killed a recipient; and, separately, a supervisor who allegedly physically assaulted a nurse and doctor; and

- countless other issues that have led to unrecovered, mishandled, lost, or damaged organs; patient deaths; and inappropriate use of taxpayer money, sparking Congressional investigations into fraud, waste and abuse.

We found oversight gaps or conflicts in 6 key areas:

- OPO failure to recover enough organs: OPOs can easily hide or manipulate their outcome measures in the current system, leading to thousands of organs going unrecovered and/or untransplated, and patients needlessly dying on the waitlist. This compromises not only oversight and regulation, but also academic research, which would ideally function as a means to inform ongoing policy considerations.

- Complaints process: OPOs are expected to self-report patient safety issues to the federal contractor tasked with optimizing their performance, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS). But, even in UNOS’ determination, the voluntary nature makes these reports “subject to underreporting.” We found that few complaints are ever lodged against OPOs due to a lack of confidence that change will occur, fear of retribution if someone makes their concerns known, and unawareness of the reporting process.

- Conflicts of interest: Committees and boards within UNOS, as well as reviewers at academic journals, are often filled with OPO leaders, board members, and/or other member representatives. This leads to situations such as leaders from underperforming OPOs deciding their own performance review process or suppressing unfavorable research.

- Communication across a diffuse government structure: The groups within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) that ultimately oversee the organ donation system are reported to have a lack of communication and collaboration.

- Financial incentives: The large gap in oversight of financial incentives and resource allocation has led to issues such as OPOs spending a disproportionate amount of resources on lucrative tissue procurement, and OPOs spending taxpayer money on things like football tickets and lobbying expenses, while under-resourcing key programming more likely to lead to life-saving organ recoveries, such as hiring and supporting frontline staff.

- Technology and security: UNOS technology is outdated, inadequate, and insecure, yet government oversight arms are not auditing it, managing it in any meaningful capacity, or otherwise holding it to an appropriate standard.

In order to realize the potential impact of the new Final Rule for OPO performance evaluation that HHS published in November 2020 — which is projected to result in more than 7,000 more lives saved every year, while saving $1 billion annually to Medicare — we believe it is necessary for HHS to make parallel reforms to oversight and governance. We believe a new, empowered Office of Organ Policy (OOP) could be the ideal structure to oversee implementation of HHS’ new accountability measures and other crucial reforms. We also recommend decreasing conflicts of interest, improving the existing survey and complaint process, and increasing transparency and data visibility to monitor stakeholder compliance with federal regulations as well as foster more competition and innovation. In parallel, Congress should play an essential role in OPO and UNOS oversight to support and inform actions taken by the OOP.

Introduction

Each year, as many as 28,000 viable organs fail to reach patients who critically need them.1 Because of the failure to recover and transplant those organs – and the continued pace of demand outstripping supply – nearly 33 people die every day because they don’t have access to an organ transplant.2

Organ procurement organizations (OPOs) are responsible for working with hospitals to recover as many organs from deceased patients as possible and to find a suitable recipient while the organ is still viable. There are 573 such OPOs spread throughout the U.S., and their performance differs dramatically.4

According to one analysis, some of the lowest performing OPOs – such as the federal contractors in Kentucky and South Carolina – recover organs from only 1 in 4 potential donors.5 This underperformance translates directly to patients dying unnecessarily on the organ waiting list, with the burdens of OPO failures falling disproportionately on people of color.6

However, none of these OPOs has ever been successfully decertified by the federal government. OneLegacy, the country’s largest OPO, was deemed, “one of the worst performing OPOs in the country” by Rep. Katie Porter.7 8 The Los Angeles-based center recovered organs from only 31% of potential donors, according to an analysis from the University of Pennsylvania on OPO performance from 2012 to 2014.9 Despite the OPO’s underperformance, OneLegacy’s CEO Tom Mone is paid more than $904,000 per year10 and its Board Chair is paid $100,000 annually with taxpayer money.11 The group also misspent more than half a million taxpayer dollars on “unallowable or poorly documented items” – including football tickets, parade expenses, and lobbying costs – according to a government audit.12 13 14 Subsequently, a Los Angeles Times investigation found OneLegacy to have interfered with death investigations through improper tissue harvesting and then to have coordinated with coroners’ offices to cover it up.15 16 Even more recently, in December 2020, OneLegacy was the subject of a Congressional oversight inquiry from the House Committee on Oversight and Reform seeking information regarding potential conflicts of interest, executive and board compensation, anti-patient lobbying, and the OPO’s use of Paycheck Protection Program loans.17

OneLegacy is far from the only OPO tainted by scandal. In Alabama, OPO leaders were sent to federal prison for participating in an illegal kickback scheme with a local funeral home.18 The former director and associate director of Alabama Organ Center (which has since re-branded to “Legacy of Hope”) pocketed nearly $500,000 in the plot involving lucrative tissue harvesting.19

In South Florida, a doctor and nurse alleged being physically assaulted by a manager of an OPO for speaking up about personnel shortages and inadequate training.20 The two women were let go; one was fired, and the other’s contract was not renewed after 17 years of working there. Meanwhile, the supervisor kept his position of leadership.21 Four years later, the same OPO nearly killed a woman for failing to identify a fungus on a uterus before sending it out for transplantation — and did so during a period in which the OPO was already deemed a “member not in good standing” due to a “serious lapse in patient safety or quality of care.”22

In South Carolina, the OPO We are Sharing Hope SC shipped lungs and a liver with an incorrectly identified blood type – killing the lung recipient and injuring the liver recipient.23 The Post and Courier, a South Carolina newspaper, noted that it was only after the news outlet started asking questions about We are Sharing Hope SC that oversight agencies said they would review the case. When investigators finally looked into the South Carolina OPO after the incident garnered news attention, they found problems with We are Sharing Hope SC’s blood-typing policies.24

Despite systemic issues throughout the organ donation system, there has not been extensive scrutiny of OPOs by oversight agencies. Additionally, there’s a lack of competition to drive performance, since OPOs operate as monopolies in their respective regions. The Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) was created to oversee OPOs and coordinate organ allocation throughout the country. However, only one contractor has ever held this position, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), and they are also rarely held accountable by federal oversight agencies. Historically, all OPO data shown to public and regulatory bodies – including reports of patient safety issues and failures to recover viable organs – have been self-reported to UNOS, allowing OPOs to mask errors and poor performances.

A new rule proposed by CMS in 2019 and finalized in November, 2020, offers new objective measures to better assess OPO performance and provides a pathway to decertification for low performing OPOs.25 The new rule is a big step forward, and we strongly urge HHS to apply the new measures to the upcoming 2022 certification cycle to enact much-needed change as soon as possible.26 The new rule also highlights just how dire the current OPO situation is: 34 out of the 57 OPOs in the country are so sufficiently underperforming that they would either be decertified or their donation service area would be opened up for competition.27 28

For the many reasons discussed so far, it is essential to identify the oversight gaps that have allowed such egregious OPO misspending, underperformance, and patient safety issues to go unremediated. As one transplant center consultant explained, “I don’t think anything on the OPO side will improve until they feel like they can’t get away with hiding things.”

Our research revealed oversight gaps or conflicts in the following 6 key areas:

- OPO failure to recover enough organs, quality control, and negligence

- Complaints process

- Transparency around conflicts of interest

- Communication across a diffuse government structure

- Financial incentives

- Technology and security

The purpose of this report is to closely examine the current governance and oversight structure of the organ donation system to identify gaps, conflicts, and impotencies. We also provide recommendations for what can be done to save more lives through organ donation and transplantation. Organ donation reform is more urgent now than ever before, given evidence that COVID-19 increases the risk of organ failure and dialysis centers pose a major transmission risk to vulnerable patients.29 30

While many of the entities and regulations in this report also pertain to transplant centers, we will be focusing primarily on the oversight of OPOs, given their monopoly government contractor status, clear documentation of their severe poor performance in organ recovery, and their financial opacity, as well as the failure of OPTN/UNOS to properly oversee them. Additionally, the oversight system for transplant centers appears to be working more effectively,31 while there is clear evidence that the oversight system for OPOs and UNOS is broken and in urgent need of addressing.

Current Reliance on Media for Accountability

Many failures within the organ donation system have either been largely ignored by regulatory bodies, or weren’t given attention until after they garnered press. As one government official told us about the organ donation system, “sometimes the best way to file a complaint is to go to the news media.” This was the path Oregon resident Erika Zak and her family took after a policy change made it more difficult for her to receive the liver she needed.32 UNOS, the federal contractor tasked with overseeing OPOs, made the policy change that resulted in a lower “score” for Erika’s placement on the waitlist. The change led to a score that was “determined not by her doctors’ careful evaluations, but by an anonymous panel of five transplant professionals who reviewed a short application,” according to the New York Times.33 As Erika’s twin sister, Jenna, told us, “Erika and [her husband] Scott were cautious about speaking to the press, but at the time they felt like they had no other options than to call out UNOS.” Before going to the press, Erika and her family wrote letters, reached out to UNOS directly, reapplied for a new score, and had her doctors argue her case. But UNOS stayed quiet, according to Jenna. The effort of taking their plight to the media “felt like a full time job,” and was a drain on their family who was already going through so much. Jenna told us that, “[s]omeone said UNOS’ strategy was just to sit it out…thinking that we would give up or that Erika would die.” Erika’s story was covered by outlets such as CNN and the Washington Post. The New York Times editorial board even profiled her case, concluding that HHS should “fix the UNOS scoring system” and “revisit the UNOS monopoly” to help address the “astounding lack of accountability and oversight in the nation’s creaking, monopolistic organ transplant system [that] is allowing hundreds of thousands of potential organ donations to fall through the cracks.”34

“Sometimes the best way to file a complaint [about the organ donation system] is to go to the news media.”

- Government official

While Erika’s story received national attention, there are thousands of organs that are lost and patients who subsequently die and never make it to the press. Relying on the media to catalyze change in this system is both insufficient and unfair. This approach leads to a reactive system of oversight, addressed by a patchwork of fixes.35 And it exacerbates inequity issues within the system. As Erika’s sister told us, “we were in a position where we were privileged to have those [media] connections. Other people don’t have those opportunities, even though they’re struggling with the same situations… it’s completely unfair. That’s not how this should work.”

While transplant centers have historically faced a wide range of scrutiny from the press,36 37 OPOs may miss a clear opportunity to recover a life-saving organ, and it’s very possible no one outside the OPO finds out or files a complaint. The scrutiny on transplant centers has led to more public inquiries from oversight agencies,38 and a wave of regulatory changes.39 However, no such wave has happened with OPOs yet.

Every organ that is not recovered because of OPO ineffective practices, transportation errors, or understaffing, results in another person dying while on the waitlist. For the purposes of this report, we have termed these “shadow deaths”; they are just as real and consequential as deaths resulting from errors that have brought higher profile media attention, but are less visible as they result from systemic rather than acute problems. This aligns with findings from our earlier research that, in the estimation of one leading researcher, “we don’t have an adequate way of expressing the harm of a non-approached donor. There are significant harms – the donor’s decision to donate may not be honored, the family may not get closure or comfort, patients on the waiting list die, and costs increase to the national health care system. And yet OPOs are able to keep these harms invisible.”40 A large oversight gap in the organ transplant system is in accounting for these “shadow deaths,” and the 110,000 people currently on the transplant waiting list deserve immediate action to address them.

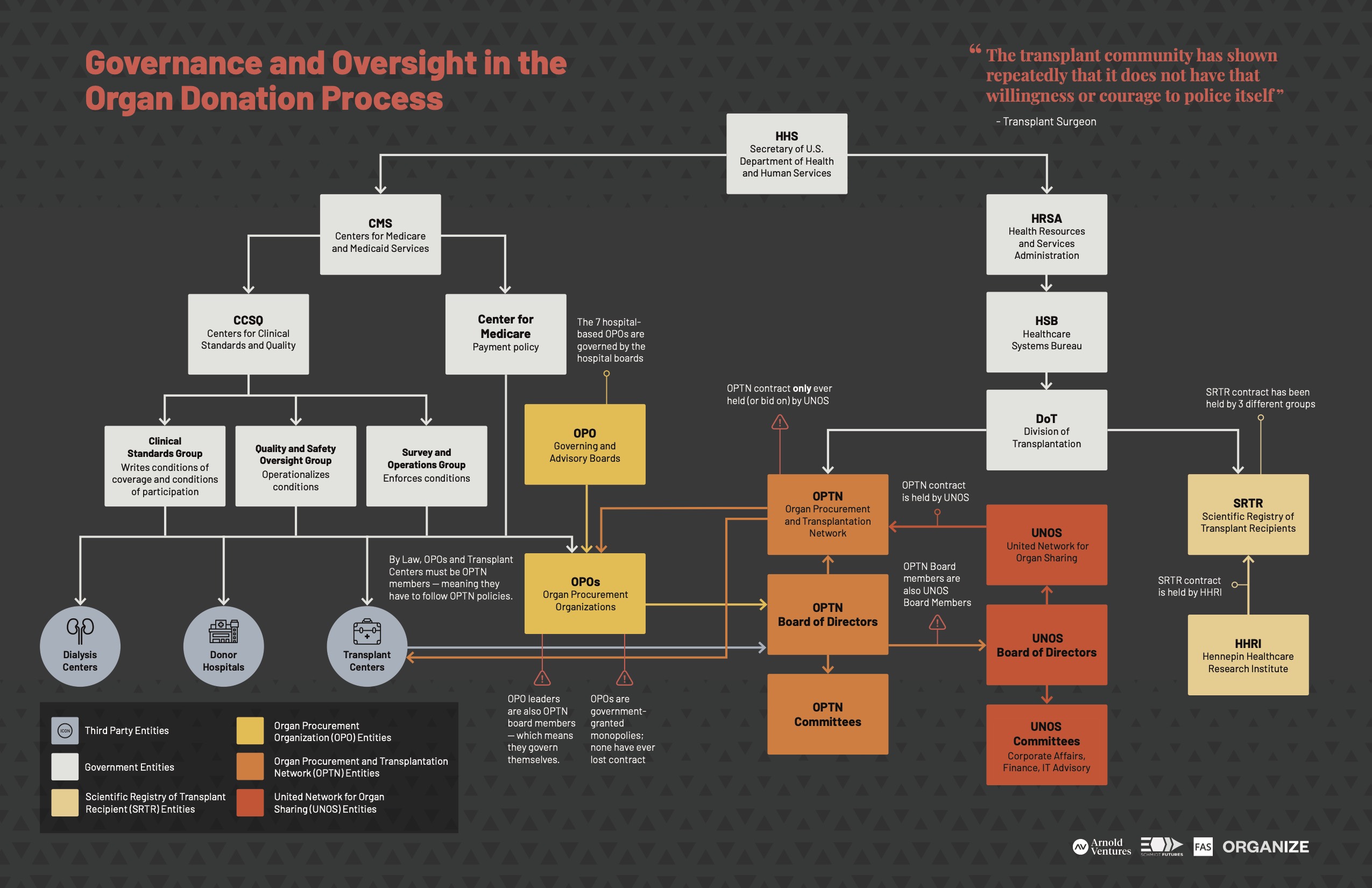

Overview of How the Governance was Designed

The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) currently oversees the organ donation system. Within HHS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is responsible for overseeing OPOs. Historically, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) was responsible for overseeing the OPTN, however as of publication of this report (January 2021), this role is being shifted to the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH).41

Download the “Governance and Oversight in the Organ Donation Process” PDF

CMS Oversight of OPOs

CMS is responsible for certifying OPOs and establishing the rules OPOs must follow – or the “conditions for coverage” – in order to be compensated for their organ recovery and placement work. CMS, specifically the Center for Clinical Standards and Quality (CCSQ) and the three sub-departments under CCSQ, are responsible for writing the conditions for coverage for OPOs, enforcing the conditions, and recertifying OPOs.42 The Center for Medicare (CM) within CMS pays the OPOs for organ recovery through reimbursements.

The 2020 Final Rule, which is projected to increase the recovery of life-saving organs by more than 7,000,43 notes that historically OPOs have not been held accountable for consistent low performance.44 CMS’ press release announcing the Final Rule stated, “[s]ome stakeholders have argued that many [OPOs] are underperformers and have faced few consequences for their poor performance. Current organ recovery and transplantation measure regulations are outdated and allow OPOs to subjectively report organ recovery rates.”45

As one transplant surgeon explained, “there’s been a tremendous amount of inefficiency and issues associated with the OPO system, [but it] has never crawled to the top of the CMS agenda.” Some within CMS perceive the overall cost of compensating OPOs as small compared to the total dollars spent elsewhere, and so therefore not worth much attention. As one senior government official told us, the historical lack of attention paid to OPOs is because “it’s such a small part of the total dollars that CMS uses and administers every year.” However, the relatively small reimbursement cost to OPOs shadows a much larger cost of OPO inefficiency; CMS currently pays $36 billion a year on dialysis and treatment for people who need a kidney transplant – more than the annual budget for NASA46 and the CDC47 combined.48 Each kidney transplant facilitated represents a lifetime cost savings of more than $350,000 per patient in avoided dialysis costs.49 50 Research estimates the U.S. could save $40 billion over 10 years by increasing kidney transplant via OPO reform.51

“Research estimates the U.S. could save $40 billion over 10 years by increasing kidney transplant via OPO reform.”

OPTN Oversight of OPOs

When the National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) was passed in 1984, it established the OPTN – a membership-based entity tasked “to improve the effectiveness of the nation’s organ procurement, donation, and transplantation system by increasing the availability of and access to donor organs for patients with end-stage organ failure.”52 All OPOs are OPTN members, and thus are expected to comply with OPTN bylaws and policies.

The OPTN contractor role has been filled exclusively by UNOS since 1986. However, while the OPTN contract is awarded by the federal government, more than 90% of the contractor’s revenue comes via stakeholders who are required by the government to be OPTN members, seemingly creating an inherent conflict; investigative reporting from the Los Angeles Times covered this dynamic, describing UNOS as a “reluctant enforcer” and noting that “[s]uch collegiality is built into UNOS’ very structure – and that’s the problem, some critics say. UNOS isn’t just a regulator; it is a membership organization, run mostly by transplant professionals.”53

Many people we spoke with reinforced this characterization, suggesting that UNOS seems more concerned with keeping their members (OPOs and transplant centers) happy than exercising legitimate oversight; in effect, shielding its members from punishment rather than actually holding them accountable.

But this need not be the case. NOTA tasks the OPTN (currently UNOS) with improving the effectiveness of the organ donation system, and gives UNOS plenty of leeway to oversee all aspects of OPO practices. Specifically, NOTA requires the OPTN to “work actively to increase the supply of transplantable organs,”54 and according to sources within the government, UNOS’ contract also explicitly charges them to “identify root causes of issues” pertaining to OPTN members, including OPOs.

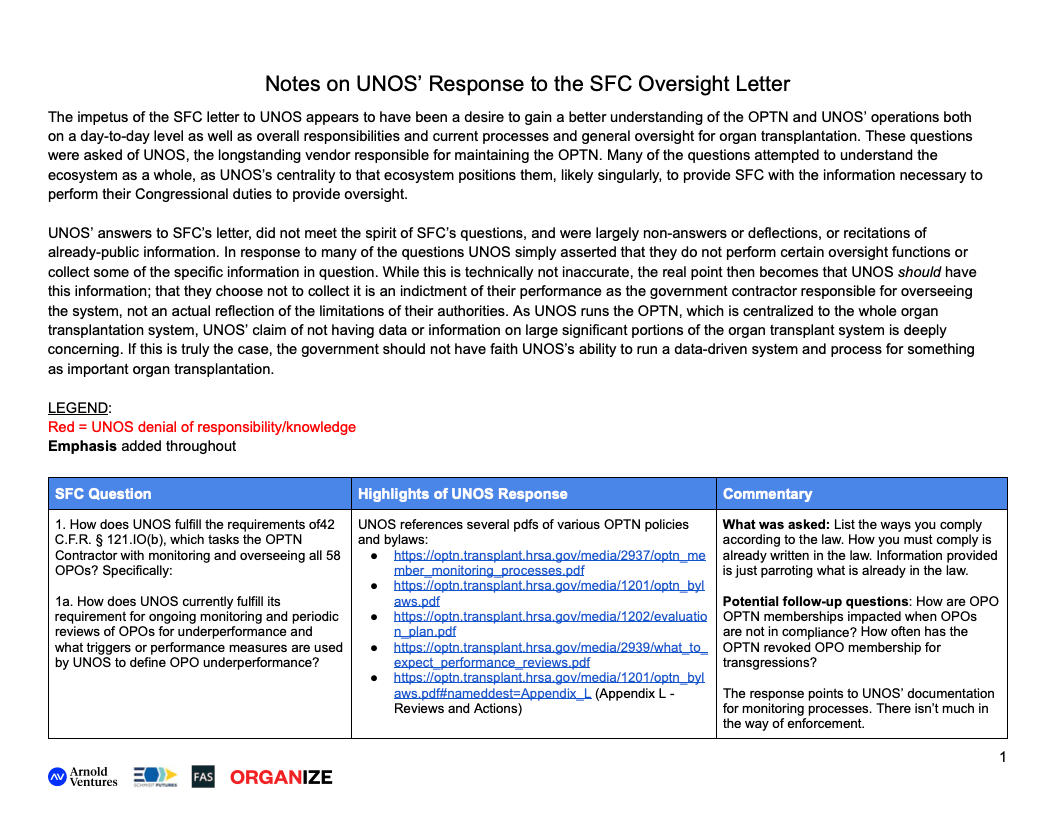

The fundamental problem seems to be that UNOS, as the sole OPTN contractor, has chosen to deny responsibility for several aspects of OPO oversight.55 For example, in response to a Senate Finance Committee (SFC) letter asking what steps UNOS has taken to address the multiple OPOs who expensed taxpayers with “unallowable expenditures,” UNOS wrote that “[t]he OPTN is not authorized to monitor or enforce CMS Conditions for Coverage [and that] UNOS and the OPTN do not require independent audits of OPOs for costs because cost reporting is not an OPTN Obligation.”56

While this may be technically true, there is certainly nothing in NOTA that would preclude UNOS from overseeing such issues. In fact, understanding OPO resource allocation would seemingly fall entirely in line with UNOS’ contractual mandate to identify the root causes of OPO performance issues. UNOS’ denial of these responsibilities is clearly a choice in how they interpret the mandate given to the OPTN, and they could be doing much more to address root issues and increase the supply of organs.57

In addition to the denial of responsibility for certain aspects of OPO oversight, UNOS also does not provide any incentive for OPOs to change. Even in the exceedingly rare instances when the OPTN determines that an OPO has violated policies, the strongest punishment that UNOS metes is to deem the OPO a “member not in good standing,” a designation UNOS has only used twice in its decades-long history.58 As one HHS official told us, “the OPTN would not take strong action against an OPO unless it was doing something unthinkably egregious, like if they were buying and selling organs.” Alarmingly, documented issues such as criminal activity of OPO executives and patient safety issues that led to death have not led to OPOs being classed as “members not in good standing.”

“The strongest punishment that UNOS metes is to deem the OPO a “member not in good standing,” a designation UNOS has only used twice in its decades-long history.”

Part of the reason for this lack of enforcement is the rampant conflict of interests within the OPTN committees that are supposed to be monitoring OPO conduct. Within the OPTN, two key committees are tasked with improving OPO and other members’ performance: the Membership and Professional Standards Committee (MPSC) and the Operations and Safety Committee (OSC).

The MPSC serves to “maintain membership criteria and monitor OPTN member compliance with OPTN membership criteria, OPTN bylaws and policies, and the OPTN Final Rule.”59 And while the MPSC, in its entirety, includes a diverse set of stakeholders across the transplant community, complaints about OPOs are first routed through smaller subsets of the MPSC to which OPO professionals are preferentially assigned. This structure seems to undercut the spirit of the Final Rule, as well as to insulate OPOs from meaningful external oversight over OPOs.60

One MPSC member we spoke with said, “my observation about participating on the MPSC is that the UNOS staff seem to persuade the committee members into taking specific actions based on how previous committee members have historically treated similar issues. Precedent seems to be the most important consideration,” and that “I will not pretend that the identity of the OPO and how well one knows the people at an OPO doesn’t influence how serious an event is perceived.”

Additionally, many of the people on these committees, and on governing boards at large, represent OPOs that are failing, according to metrics in HHS’ November 2020 Final Rule.61 62 This means that staff from underperforming OPOs are creating their own performance review process, bringing into question just how effective the review process is designed to be.63 Additionally, while the OPTN and MPSC technically employ a conflict of interest policy, their chosen definitions for such conflicts are overly narrow, likely missing many actual conflicts.64 Compounding the problem, MPSC proceedings are protected by peer review, so there is no transparency around whether OPO leaders are using the process for personal or professional gain or advancement, or the extent to which cronyism protects OPOs favored by the MPSC.

The OSC, which is responsible for “improv[ing] the quality, safety, and efficiency of the organ donation and transplantation system,”65 creates suggested practices for all members to improve performance, but these are largely voluntary and do not stand alone as compliance measures. As one former MPSC chair informed us, the MPSC “never spoke about operations stuff” nor discussed issues at a systems level. These two committees do not collaborate to address systemic problems by identifying where OPO failings are a trend, but instead focus only on one-off incidents. In other words, massive underperformance – and therefore “shadow deaths” from organs not recovered – does not seem to rise to consideration of the MPSC, despite organ recovery being the central function of OPOs.

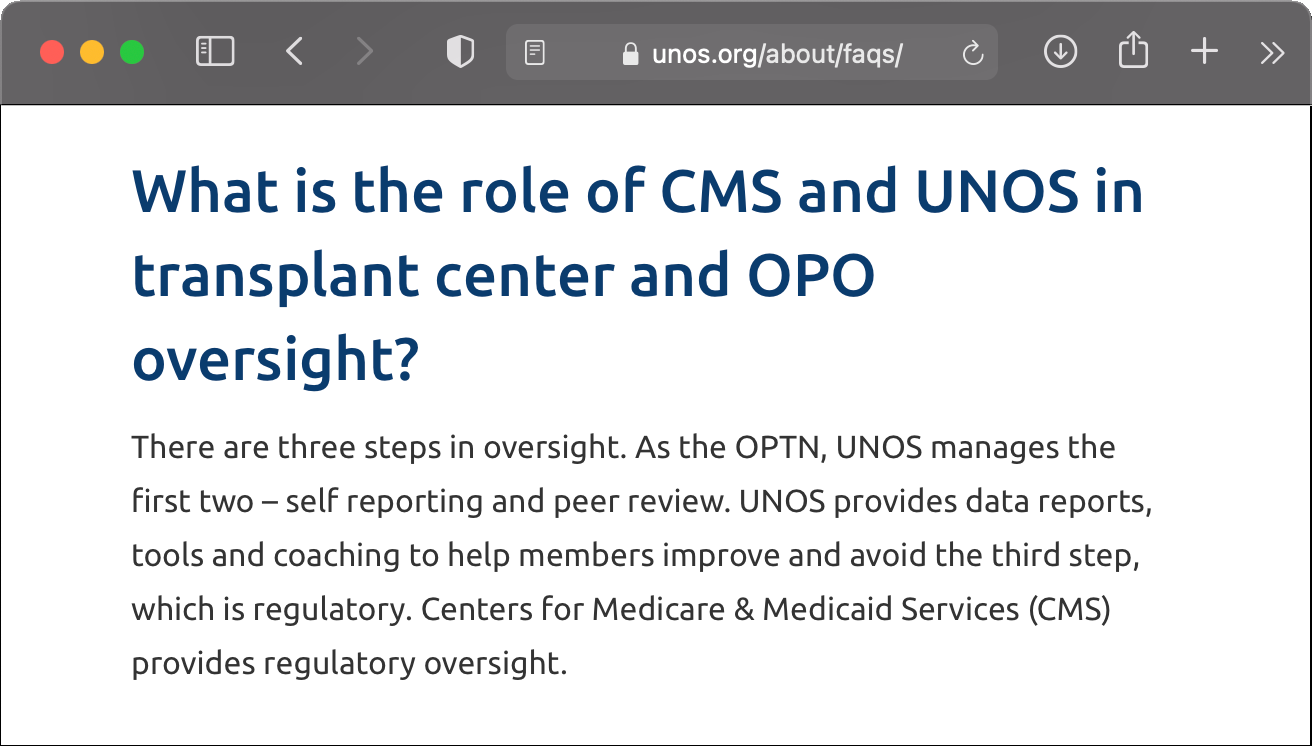

Tellingly, even UNOS appears to have previously acknowledged its role in providing oversight. As of February 2020, in the FAQ section of UNOS’ own website UNOS stated that it “manages the first two [of three] steps” of “OPO oversight.” Only after the Senate Finance Committee opened an investigation into UNOS’ abdication of such oversight did UNOS change the language on its website to distance itself from oversight responsibilities, stating: “Many people think UNOS oversees every facet of the transplant process. We don’t…UNOS is a forum for organ donation and transplant professionals to come together and determine how the national system should work.”66 According to one MPSC member, “[if UNOS actually wanted to], they could put their hands on OPO failures much more seriously than they have in the past.”

In any case, one of two things must be true: either the OPTN is responsible for such oversight and has been delinquent in exercising its authorities, in which case HHS should consider UNOS’ track record in future contracting cycles; or HHS can determine that the OPTN is not responsible for such oversight, and, by logical extension, should then reabsorb such functions into an Office of Organ Policy to ensure that OPOs are meaningfully regulated on behalf of patients and taxpayers. We note however, that in the first instance, regulatory capture could remain a persistent concern.67

Similarly, we have heard from stakeholders that the executives, staff, or analysts from the Scientific Registry for Transplant Recipients (SRTR) are allowed to engage in private consulting work for individual OPOs. This is a problem, because SRTR is supposed to be providing unbiased policy research to HHS regarding OPO performance. If executives within SRTR are viewing OPOs as potential clients, they might have the potential to distort their findings. According to one longtime OPO executive, “I had no idea about this until recently, and I was floored! It also amazes me that AOPO [the Association of Organ Procurement Organizations] consults with the SRTR about OPO performance data and the OPO regulation, and that the SRTR was actively assisting in discrediting CMS’ proposed OPO rule. In effect, a HRSA contractor was trying to help AOPO undermine CMS.”

HRSA’s Historical Oversight of the OPTN and UNOS

As mentioned above, HRSA is currently phasing out of its role in overseeing the OPTN. The Division of Transplantation (DoT), which previously lived under HRSA and will now live under Assistant Secretary for Health (OASH), is tasked with contracting out the role of the OPTN and overseeing its function.

One problem we heard from multiple interviewees is that NOTA – the 1984 law that created the OPTN – has been very narrowly interpreted. Since it was established, NOTA has been interpreted to require the OPTN be operated by a single, private contractor. This interpretation of the law, while up for debate, has been a major blocker in instilling unbiased oversight, as well as serving to suppress meaningful competition for the OPTN contract.68

According to one government official we spoke with, HRSA historically tried to break apart the OPTN contract so one expert contractor could manage the technology portion, while another contractor managed policy-making, and another managed member evaluation. This would theoretically reduce monopolism, anti-competitive behavior, and conflicts of interest, while allowing for more expertise to be used for the very different functions. Research has identified major technological shortcomings in the current OPTN contractor’s software, showing an urgent need to seek out a better vendor solution.69 However, these historical attempts to find flexibility had been met with resistance, according to our interviewees, although the incoming Administration should consider ways to increase flexibility in order to better serve patients.

HRSA lives within HHS. As one senior government official explained, another issue was that HRSA had little influence compared to other agencies in HHS – which, as they explained, leads to pressure for them to “not rock the boat” or upset the larger agencies. This also made it difficult to practice effective governance over the OPTN. HRSA’s role (and now OASH’s going forward), as the main government representative in OPTN committee meetings, is to ensure the obligations of the OPTN contract are being fulfilled. However, we were told by several interviewees that HRSA representatives often lacked the expertise to discern whether what was being said and decided was appropriate.

OPO Board of Directors

Even in the context of a breakdown in governmental oversight, an OPO’s board of directors, in line with their fiduciary responsibilities, can still wield considerable influence on OPO performance. However, many stakeholders we talked to suggested that many OPO boards are plagued by ineffectiveness, conflicts of interest, and inconsistent governance. “[OPO leadership] are not accountable to anybody but the people they choose to be on their boards,” explained one former government official, “so it serves them to have people on their board who are their buddies.”

“[OPO executives] are not accountable to anybody but the people they choose to be on their boards, so it serves them to have people on their board who are their buddies.”

- Former government official

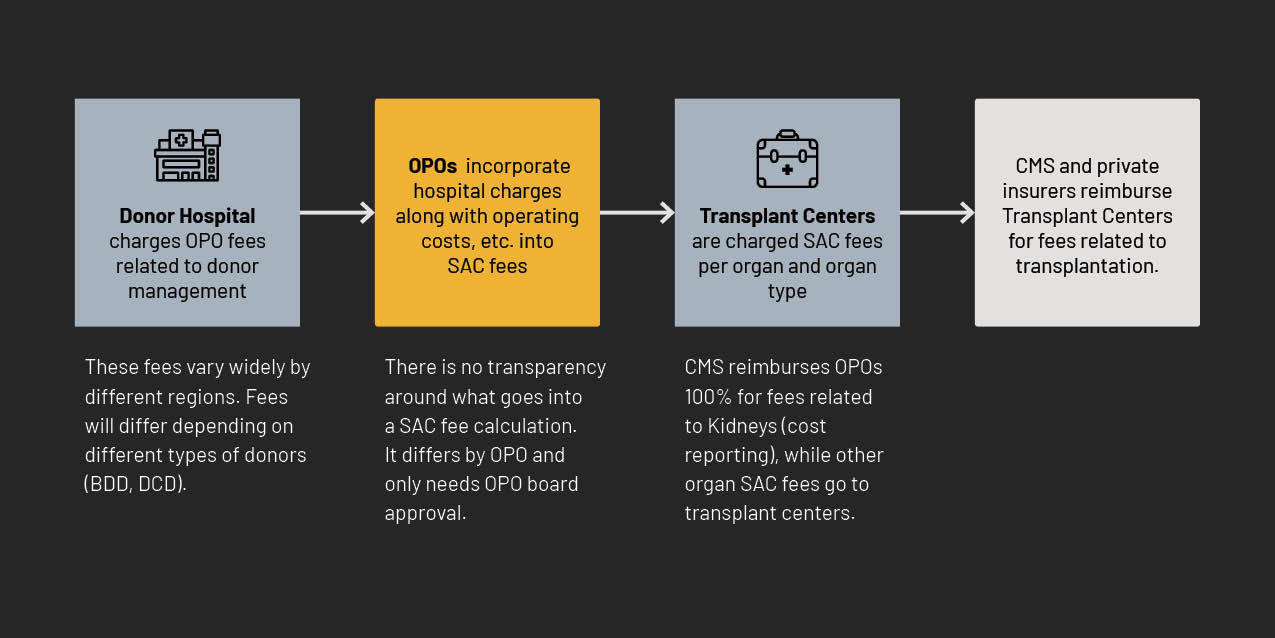

Some OPOs further incentivize their board of directors to cooperate by paying them for various services.70 For example, OneLegacy, the Los Angeles OPO, which under the November 2020 outcome measures was flagged as tier 3 “failing,”71 nevertheless pays its board chair, Bill Chertok, $100,000 and other board members $30,000 or more.72 Despite being one of the worst performing OPOs, as well as having been found by the HHS Inspector General to profligately misspend taxpayer funds, it appears the CEO is insulated from being replaced because of such payments.73 Given that OPOs are essentially reimbursed 100% through Standard Acquisition Charges (SAC fees) and CMS reimbursements,74 it is not a cost to the CEO of OPOs to pay board members, but rather a cost to taxpayers. Additionally, while OPOs are technically not allowed to receive reimbursement for lobbying expenses, board compensation creates a loophole. For example, an OPO can compensate a politically-connected board member and leverage such access, which would not technically qualify as lobbying.75

While NOTA prescribes the composition of OPO advisory boards – which include clinicians, such as transplant surgeons and hospital representatives – there are currently no regulations for who is on an OPO governing board. The advisory boards make general recommendations to the board, but it is the governing board that decides whether or not to act on them. One HHS official shared that there have been high-level discussions about the need for more regulations around who is on the OPO governing board, and agreed that there should be requirements around qualifications and type of representation. However, it is uncertain what authorities HHS has to direct the composition of the OPO governing board, which has led to highly inconsistent roles, policies, functions, and effectiveness of OPO governing boards, allowing poor OPO performance – and rampant “shadow deaths” – to persist. 76

Even when an OPO board of directors means well and has the right qualifications, it is often limited by the data that they’re shown by the OPO. One OPO board member we spoke with said the lack of shared data regarding OPO performance hampers the ability for general improvement. “The OPO board is only as good as the information they get… The evaluation tools that we get to show us how we’re doing compared to other OPOs aren’t helpful. They all give us a false sense of security that everything’s fine. A lot of OPO boards don’t get comparative data, they don’t get to see what their peers are doing.” One OPO CEO who helped turn around an underperforming OPO in less than a year explained that one board member’s response was: “We have to let everyone know that the OPOs are broken. I personally feel duped that I’ve been told all these years [that] we were doing everything we could.” This problem is exacerbated by UNOS and OPOs, which regularly herald record organ donation rates, despite peer-reviewed research showing that this is due to the opioid epidemic and not OPO improvement.77 78

Diffuse Governance and Why That’s a Problem

Multiple people we spoke with pointed to the lack of coordination and conflicting tensions between the various arms of oversight as being one of the largest problems within organ donation. “Governance of organ donation is remarkably diffuse and not terribly well coordinated,” explained one HHS official. Others characterized organ donation oversight as too big for HRSA and too small for CMS. While this may be perceived as a relatively small cost for CMS when only considering direct OPO reimbursement, it is a massive expense when we consider the dialysis costs79 stemming from OPO failure to recover enough kidneys for patients who could have been transplanted but were not. Thus this lack of effective oversight is not only costing lives but also taxpayer money.

Oversight coordination has become a topic of congressional interest, as a recent letter from the Senate Finance Committee to HHS requested: “Please provide all documentation regarding coordination between HRSA, CMS and the OPTN contractor (currently UNOS) related to the following three cases involving lapses in patient safety.”80

CMS handles the money and ultimately determines whether an OPO is certified (and thereby eligible for CMS reimbursement for services). Pertaining to deceased donation, the Department of Transplantation (DoT) (formerly under HRSA and going forward under OASH) is charged with awarding and managing the OPTN contract, and has indirect influence over the waiting list and organ allocation. But the lack of clear delineation of responsibilities between oversight authorities (HRSA and CMS as agencies and UNOS as the current contractor operating the OPTN) has historically led to many inefficiencies in an ecosystem that would benefit from more streamlined and holistic policymaking. “It is unclear as to what the individual responsibilities are. And that’s the kernel of the issue,” said one UNOS board member.

“It is unclear as to what the individual responsibilities are. And that’s the kernel of the issue.”

- UNOS Board Member

The “quasi-governmental” nature of the OPTN has also opened questions about which entity is accountable in various and all-too-commonly occuring scenarios: the OPTN (currently UNOS), HRSA, or CMS. The path to accountability has been further muddied by the sweeping language within NOTA, and the discrepancies in interpretation across the OPTN.

Gaps and Conflicts in Oversight

Key areas of oversight gaps we identified include: OPO poor performance and negligence, the reporting process for complaints and misconduct, transparency about (and lack of meaningful prohibitions against) conflicts of interest, cross-governmental communication, financial incentives, and technology and security.

We share these findings with the intention of shedding light on the aspects of the organ donation system that need better accountability and oversight, with the ultimate goal of recovering more organs and saving more lives. We are aware that some stakeholders within the system have argued that highlighting these issues may undermine public trust in the donation process and lead to fewer donations, but historically such attention simply has not had any depressing impact on donation rates. For example, even in an extreme case of bad press regarding a transplant surgeon charged with felony murder in 2008 for allegedly hastening someone’s death in order to recover transplantable organs, the Los Angeles Times found that the case had “not dampened organ donations.” And that according to a spokesperson for the Los Angeles OPO, “consent rates at hospitals go up and up.”81

In reality, media spotlight on shortcomings in the system has been a crucial tool in effecting change. Members of Congress,82 83 including those in the Senate Finance Committee and the House Committee on Oversight and Reform,84 have cited several investigative journalism pieces as evidence of why OPOs need to be held to higher standards.85 86 87 The Congressional letters boosted by the media pieces helped usher in the Final Rule, which is projected to lead to thousands more organs recovered, and thus save thousands of lives. Research suggests that heightened scrutiny of OPOs – resulting from increased awareness of OPO failures – actually likely has a positive effect on donation rates. A report from the Bridgespan Group, citing data from leading researchers in a public comment to HHS regarding the then-proposed OPO rule, found: “Since the executive order announcing the proposed new metrics and increased oversight, data show that OPO performance has already begun to improve, perhaps early evidence of the ‘Hawthorne effect’ (i.e., increased scrutiny and observation by itself drives behavior change that leads to improved outcomes).”88 89 In fact, according to patient advocates, when legislators assume goodwill within the organ donation system, it can block further scrutiny and stall reforms that would strengthen the system and save more lives. 90

OPO Failure to Recover Enough Organs and Negligence

OPO failure to recover enough organs and negligence is a key area that reflects major gaps in oversight. As mentioned earlier, OPO performance varies widely. Until the November 2020 Final Rule, OPO regulation relied upon self-interpreted, self-reported data, which made it easy to manipulate. As one OPO leader told the New York Times, “I used to work at an OPO, and we reported false numbers to make it appear we were doing better than we were.”91

Circularly, such data reporting issues have also made it impossible for the government to actually decertify OPOs or otherwise hold them accountable.92 The Association of Organ Procurement Organizations (AOPO), the trade group representing OPOs, has argued that because data is self-reported and unverifiable, “the accuracy and consistency of data cannot be assured.”93 This is the same argument that prevented CMS from decertifying the Arkansas OPO in 1999, despite the OPO failing four out of five performance measures then in use; a federal judge agreed with the OPO’s case that CMS could not rely on the OPO’s faulty data as the legal basis for decertification.94

Our research also revealed several additional problems with current OPO accountability measures, specifically the following:

- Ineffective site surveys

- Unregulated and ineffective transportation of organs

- Absence of process metrics and data

- Understaffing

Ineffective Site Surveys

Aside from their self-reported data, the primary ways OPOs are evaluated come from infrequent site surveys conducted by UNOS, CMS, and – optionally – the Association of OPOs (AOPO). The UNOS site surveys do not measure how well an OPO performs at recovering organs, but rather how compliant an OPO is with OPTN policies. Given that, as outlined above, the OPTN is greatly influenced by its OPO members, this process can become more of a checkbox for UNOS to go through the motions of an evaluation rather than any true scrutiny and oversight of OPO conduct.

UNOS only reviews data from OPO’s electronic health records (EHRs) and compares it to DonorNet (the OPTN technology that matches organs with patients on the waiting list). In their audit, UNOS does not cross reference DonorNet data with donor hospital records to ensure the information is correct and accurately reflects the OPO’s performance. This is a huge gap in ensuring accurate reporting by OPOs. OPOs can easily manipulate the data by only entering information into their system that casts them in a favorable light. For example, if an OPO was not able to respond to a potential donor referral in time because of understaffing, they could leave the patient record completely out of their EHR records or put another reason as to why the referral did not become a donor. In effect, UNOS is simply auditing whether the OPO’s reporting is internally consistent (even if incomplete or misleading), rather than actually assessing the OPO’s performance.

“UNOS audit is a joke. All that the UNOS auditors do are come in and say, ‘do you meet the policies and requirements that are set forth, yes or no.’ They are not there to improve things…There’s nothing that tries to push you further.”

- OPO consultant

As one OPO consultant explained, “UNOS audit is a joke. All that the UNOS auditors do are come in and say, ‘do you meet the policies and requirements that are set forth, yes or no.’ They are not there to improve things…There’s nothing that tries to push you further.” Another OPO leader shared, “[the site survey] is not a survey that will tell you how good an OPO we are. It will tell you how compliant we are with the administrative and clinical policies that they [the OPTN/UNOS] have.”

Governmental surveys are likewise fraught. Several people we talked to said CMS surveys were conducted by surveyors without proper subject matter expertise to truly assess the organ donation process. As one OPO leader said, “these are the same surveyors as those inspecting meat packing plants.” Even surveyors with medical facility expertise would miss many of the problems of an OPO operation because OPOs do not function in the same way as hospitals and other medical providers. Other people we spoke to said the CMS survey required a lot of paperwork, but that it was easy to “spin it” to the auditors.95 As another HHS official shared, “it’s clear that CMS doesn’t have the expertise to be able to have oversight [of OPOs] effectively… We need surveyors who understand the nuances, and can identify problems more effectively.”

Most OPOs volunteer to participate in a third optional survey by AOPO, to get accredited as an AOPO member. But since AOPO is not an oversight body, findings from such surveys do not lead to any consequences for an underperforming OPO. Some OPOs find these surveys to be more helpful because it has fewer consequences from an oversight perspective. As an OPO leader shared, “when AOPO was coming in, I always told staff ‘be honest’ because what you say to them is not going to change our being funded, it’s not CMS. We’re choosing to be accredited, so if there is something that would drive additional staffing, supplies, or technology resources that’s needed, this could come out of the AOPO survey. CMS is not the place you encourage staff to say, ‘yeah, we’re understaffed and we can’t keep up the call schedule,’ because of course everyone worries you’ll be slapped on the hand and lose funding.” However as an OPO executive informed us, AOPO surveyors are staff from other OPOs, some of which are low-performing OPOs or may be friends of the OPO they’re surveying, so there is often an inconsistent relationship between the standards and how effectively the OPO is performing. While they may provide some value, optional and consequence-less surveys from the OPO trade association should not be confused with, or used to crowd out, necessary oversight.

Unregulated Transporting of Organs

There are also troubling gaps in what surveys examine. One of the many things that the site surveys don’t look at is how well organs are being transported to where they need to be for transplantation. Organs lost or delayed in transit directly lead to patients dying on the waitlist or suffering worse clinical outcomes due to increased cold ischemia time of the organ.

Evidence shows that transportation failures are a common occurrence. For instance, a recent Kaiser Health News investigation found that hundreds of organs have been lost, damaged, or delayed in transit, “often rendering [the organs] unusable…[and that this happens because organs] are typically tracked with a primitive system of phone calls and paper manifests, with no GPS or other electronic tracking required.”96 Based on the numbers reported, organs appear to be getting delayed or lost on a weekly basis.97 Both organs transported through the OPO, as well as those by the UNOS Organ Center, have experienced significant delays, damage, and costs. Despite CMS conditions for coverage for OPOs that explicitly state that, “[t]he OPO must develop and follow a written protocol for packaging, labeling, handling, and shipping organs in a manner that ensures their arrival without compromise to the quality of the organ,”98 to our knowledge no oversight investigation has been performed by CMS resulting from Kaiser’s reporting or subsequent Congressional inquiries,99 and the OPOs responsible still have not experienced any repercussions from CMS.

The OPTN, whose role is to promote “efficient management of the [organ donation] system,”100 has no standard policy around transportation, so each OPO does it their own way. This is despite an explicit obligation in UNOS’ contract to “provide technical assistance to OPOs, 24 hours/day, every day of the year, in organ placement to facilitate matching, transporting, and sharing of organs, and to monitor and reduce organ discards resulting from logistical issues in the system.”101 In a seeming abdication of its mandate to assist and monitor OPOs in this process, when questioned about its role in organ transportation by the Senate Finance Committee, UNOS responded that “the OPTN does not collect transportation data on a national, systematic basis” and that “[m]atters involving the transportation methods used by organ procurement organizations (OPOs) are arranged directly between OPOs and transplant centers.”102

It should also be noted that UNOS directly handles a subset of organ transportation cases via the UNOS Organ Center, the deficiencies of which were reported on in the Kaiser Health News expose. When the Senate Finance Committee asked UNOS about the findings highlighted in the expose, UNOS stated that they had only started recording data for organ transport handled by the UNOS Organ Center as recently as 2016.

UNOS responded that 409 organs transported by the UNOS Organ Center have experienced transportation issues since 2016, and of those, 133 organs were never transplanted.103 This means that UNOS itself, as the OPTN contractor that is supposed to oversee OPOs, is responsible for hundreds of organs being transported in ways that have led to delays and damages, ultimately resulting in more than 130 “shadow deaths”104 of patients who were never able to receive those organs.

Importantly, as UNOS also noted, these transportation cases handled by the UNOS Organ Center represent only a “small subset of organ transportation arrangements” and that the “vast majority of organ transportation arrangements are not facilitated by the UNOS Organ Center.” By extension, it is reasonable to assume that the real total of organ transportation failures are likely orders of magnitude larger than what Kaiser Health News was able to report; however, because of UNOS’ failure to capture and report complete and transparent data, we still do not know the exact number of organs that incur damage due to transportation issues across all OPOs. We also don’t know the full extent of harm caused to patients as a result, including the total life-years lost to patients because organs were never transplanted or because the quality of an organ was degraded as a result of a travel delay.105

In addition to the transportation cases covered by Kaiser Health News, several transplant surgeons we spoke with described severe problems with organs in transit, including:

- Receiving a frozen kidney, packaged incorrectly by OPO106

- Receiving an damaged organ with tire marks on the box

- Failing to receive a pancreas that was locked in an airport locker and never picked up by a courier

Each of these instances results in a patient’s death, given that one fewer organ is used for transplant. And yet, so far as we could tell, none led to investigation or action by UNOS despite physicians alerting UNOS to the problems. Whether physicians also alerted CMS in these instances is unclear; which is itself telling that there is not a belief that the government will act.

Absence of Process Metric and Data

One of the biggest gaps with the OPO oversight is that HHS does not evaluate key process metrics, such as: hospital referral trigger criteria; triaged referral responses by OPO; response time to referral; adherence to donor management guidelines; discard rates; organ acceptance rate; consent rates; adherence to consent process; consent not recovered; or adherence to organ/tissue labeling. According to a former CMS official, “there are no real process measures that measure their effectiveness. And [those process measures are] all over the map depending on the OPO.”

The metrics evaluated by CMS are all for outcomes, which are currently fraught for reasons discussed earlier, and even HHS’ new Final Rule for OPOs does not take effect until the next OPO contracting cycle in 2022 (with failing OPOs possibly not being decertified until 2026). Not only is this bad for evaluating and overseeing OPO performance, but it also gives OPO a false sense of confidence in their performance when the data is not aggregated and shown in the context of all 57 OPOs. As one OPO CEO told us, “the number one thing is, we think we’re doing fine. That’s the irony of all this. All of the evaluation tools that we have from CMS, OPTN, tell us we’re doing fine…. Nobody in an oversight capacity, nobody at CMS, no one at HRSA, no one at HHS knows enough to tell us anything differently…That’s the big problem.” One transplant surgeon reinforced this assessment, noting that “there’s a big gap between the organs available and where we start reporting.”

“The number one thing is, we think we’re doing fine. That’s the irony of all this. All of the evaluation tools that we have from CMS, OPTN, tell us we’re doing fine…. Nobody in an oversight capacity, nobody at CMS, no one at HRSA, no one at HHS knows enough to tell us anything differently…That’s the big problem.”

- OPO CEO

Data on these process metrics are needed to establish industry standards for OPOs to measure against and gain a truer understanding of their performance. This can also help OPOs better understand some of the root causes driving poor outcomes, especially as UNOS has seemingly eschewed this responsibility.

OPO Understaffing

One of the root causes identified for OPO failure to recover organs is chronic understaffing. As one OPO leader told us, “OPOs really need to stay overstaffed so that they can meet the demands when there’s an influx of potential donor referrals, but they don’t like to do this because of cost.” (Note: since OPOs are 100% reimbursed for costs,107 OPO understaffing more often results from OPO misallocation of resources rather than OPO resource-constraint.)

While there is regulatory language around staffing from both CMS and the OPTN, functionally, neither entity closely examines nor addresses the issue of understaffing. Data on OPO staffing has long been a subject of research interest, though neither AOPO nor individual OPOs have volunteered such information, nor has HHS mandated its disclosure. While CMS requires in its Conditions for Coverage that “OPOs must have a sufficient number of qualified staff,”108 this language is very broad and does not specify how to evaluate what is considered ‘sufficient’ staff, nor does it address the chronic issue of OPOs not having enough staff to meet the peak needs when they occur. There is also no indication that CMS has initiated any investigations in response to reports of an OPO being “short-staffed at critical moments.”109

UNOS similarly does not identify understaffing as a systemic issue that results in organs not being procured. When asked about it by the Senate Finance Committee, UNOS cited that there is language in the OPTN bylaws that, “Each OPO must have the necessary staff to recover and distribute organs according to OPTN obligations” but functionally, all that they require is for OPOs to notify the OPTN when their administrative director or medical director changes.110 Supposedly, UNOS will initiate a patient safety/non-routine compliance review if they learn of staffing shortages, but there is no evidence that any OPO has experienced repercussions from UNOS for staffing storages. Even in response to a direct question from the Senate Finance Committee on how UNOS responded to a media report about an understaffed OPO that resulted in the failure to recover organs, UNOS could not provide any information.111

One former OPO leader we spoke with recalled a time when a 40-year-old candidate for organ donation passed away and his organs were never recovered. “It just boiled down to staffing. Someone had worked 26 hours, and no one was there to recover the organs. [The OPO should have] made sure there was staff there for every opportunity.” Cases like the 40-year-old candidate not getting recovered are often either categorized as a “missed opportunity” or not reported at all. But as an OPO leader explained, it’s more than a missed opportunity, “it means more people died overnight that could be alive right now… just because we didn’t read the obituary doesn’t mean someone didn’t die.”

Not only are OPOs understaffed, but the staff they do employ also does not appropriately reflect the communities they serve. Studies have found that donation rates are higher when OPO staff discussing organ donation with donor families are the same ethnicity and speak the same language,112 113 yet OPO staff remain overwhelmingly white114 and often speak only English.115 This impacts donation rates, which in turn lowers the chances of people of color finding a suitable match – as recipients are most likely to match with a donor of the same ethnicity.116

Process for Reporting Complaints and Misconducts

In addition to oversight gaps in OPO underperformance, we investigated several avenues for how people can lodge a complaint when there is OPO or OPTN misconduct. We learned that complaints are actually seldom officially lodged against OPOs or UNOS, generally for three main reasons:

- Fear of retribution if someone makes their concerns known

- Lack of confidence in the system that a complaint will lead to change

- Unawareness of the reporting process for a complaint

One transplant consultant explained to us, “if I had a complaint, I probably wouldn’t go anywhere. The messenger usually gets shot, so knowing what I know, I wouldn’t go to UNOS or CMS.” Several interviewees were unaware of how they would even start the complaint process, though many said they never looked deeply into it because they had so little confidence that anything would change even if they did complain. When we asked a transplant surgeon where he’d go to file a complaint about some of the problems he had seen, he said, “I honestly don’t know, because I have never gotten that far.”

One interviewee we spoke with witnessed UNOS’ Organ Center dangerously advise an OPO to misclassify an organ with a communicable disease. “I saw in real time suboptimal performance from the [UNOS] Organ Center that could have endangered patients…The gaps in what the contractor has provided to the OPOs are so apparent. They don’t know how to do their jobs on a very basic level to recover a deceased donor with an additional comorbidity…I really should have reported them to the MPSC, but they [UNOS] are the MPSC.” Instead of taking steps to address its dispensing of improper — and likely dangerous — advice, UNOS ended up investigating the interviewee and the OPO for going against the UNOS Organ Center’s guidance and placing an “out of sequence” organ. The interviewee said their employer ended up getting investigated by UNOS and explained that “those guys made our life hell.”

“A big reason no one reports anybody is fear of retaliation,” said a transplant center consultant. Researchers we spoke with mentioned taking great pains to avoid getting on UNOS’ or the OPOs’ “bad side” since they rely on data access and “letters of support” from UNOS and OPOs to apply for grants. Several researchers suggested UNOS made it exceptionally difficult to receive data requests if they knew the seeker was a researcher who was critical of UNOS. Peer reviewers for research papers are also often in UNOS or OPO leadership positions and may discredit research that is unfavorable to UNOS or OPOs. This results in researchers not feeling empowered to find and share truths that could help improve the organ donation field as a whole. Given that most policy is informed by peer-reviewed research, the stifling of research that challenges the status quo serves to further ossify the current, unaccountable system. Alarmingly, some transplant surgeons have also voiced concern that, if they speak out against UNOS, their patients would be disfavored in future UNOS organ allocation policies. Whether or not this concern is well-founded, it is telling that such an environment has been created in which this belief would be held and that it serves to chill dissenting opinions.

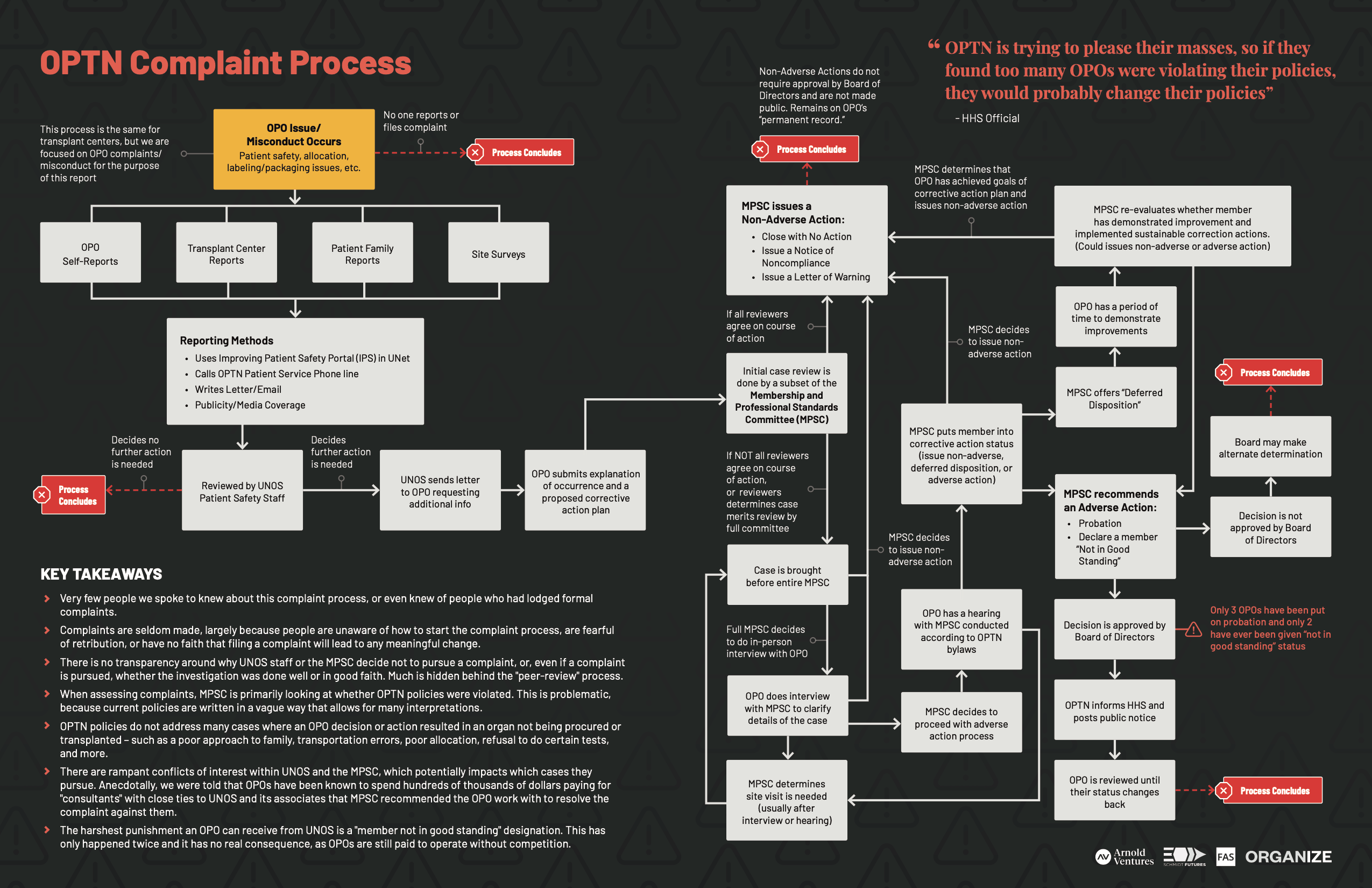

Even though many complaints are never made for the reasons explained above, formal complaint processes do exist through UNOS and CMS. However, the effectiveness of these processes are highly questionable given the dearth of substantial change that has resulted from either process. If an OPO experiences a patient safety issue or deviates from an established policy, it is expected to self-report the issue to UNOS through the Improving Patient Safety (IPS) portal.117

As we heard from OPO leaders, these deviations may include:

- a “miss” – when a procured organ does not make it to a transplant surgeon while it is still viable;

- a “near miss” – when transportation delays cause an organ to nearly miss the window of a viable transplant;

- And an “out of sequence placement” – if an OPO bypasses the UNOS matching algorithm and places an organ to someone further down the list.

“There really is no incentive, other than the integrity of this organization, to self report. Unless it’s something pretty egregious or if a center reports us, I’m confident there are a lot of OPOs that don’t self report that much…[UNOS] doesn’t do anything to really encourage transparency in the system.”

- OPO leader

OPOs are expected to submit their reports explaining what happened. However, as even UNOS admitted, “[s]ince reporting is voluntary, [it] is thus subject to underreporting.”118 As one OPO leader said, “there really is no incentive, other than the integrity of this organization, to self report. Unless it’s something pretty egregious or if a center reports us, I’m confident there are a lot of OPOs that don’t self report that much…[UNOS] doesn’t do anything to really encourage transparency in the system.” One OPO leader expressed that OPOs are disincentivized to self report, because they have a “permanent record” with the OPTN that is never expunged, even if they fix the issue. As an organization tasked with optimizing the network of organ donation, it is troubling that UNOS is not capturing critical data on misconduct more accurately, when those actions contribute to thousands of shadow deaths each year.

UNOS’ patient safety department reviews OPO self-reported submissions, along with any complaints from the public through emails, calls, or media coverage and decides whether or not to send them to the MPSC to review. The MPSC can then decide whether or not to conduct a peer-review trial investigation and move through steps to take corrective action. (See OPTN Complaint Map.) This peer-review process, including the process by which the MPSC decides which cases to review, is not open to public scrutiny.

OPTN Complaint Map

Download the “OPTN Complaint Process Map” PDF

In its response to the Senate Finance Committee inquiry about OPO misconduct, UNOS hid behind this peer-review process, citing, “we respectfully cannot provide these materials because they are privileged, confidential medical peer review information [and that] the success of our member improvement processes are critically dependent on the trust our members have in the confidentiality of this process.”119 Further review would suggest this is a logical fallacy, however, as MPSC members should not have any reasonable expectation of the confidentiality on which UNOS suggests their peer-review participation relies. This peer-review protection privilege does not extend to withholding documents from the HHS Secretary, according to the OPTN Final Rule120 and OPTN Bylaws (as of August 2020). As specified in the Bylaws, “the OPTN Contractor is required to provide the Secretary with any information acquired or produced under the OPTN Contract, including information that would otherwise be protected by the medical peer review privilege.”121

UNOS has even been forced to turn over peer-review protected information in the past after they received a subpoena from the HHS Office of Inspector General (OIG). At the time, UNOS appealed the subpoena – also on the grounds that it would undermine their future peer-review processes – though the judge ruled in favor of the OIG, writing “the inquiry is clearly within the authority of the agency [HHS OIG], the demand is clear and the information sought is reasonably relevant.”122 Going forward, Congress can use this case as precedent for future subpoenas. HHS should leverage its existing oversight authorities to access information, even absent a subpoena, and perform an audit of historical MPSC proceedings to assess the efficacy and fidelity of the MPSC process.

“Even if an OPO is deemed “not in good standing,” or put on “probation,” it is still able to function as a monopoly establishment in their designated area, and receive payment from CMS.”

Even when a misconduct is identified, the highest degree of punishment an OPTN can impose is changing a member’s status to “not in good standing,” which leads to a public announcement, but very little functional consequence. In the history of UNOS, only two OPOs have had their status changed to “member not in good standing.”123 Of those two, one had some media coverage, and the other did not. Even if an OPO is deemed “not in good standing,” or put on “probation” – the designation before being “not in good standing” – it is still able to function as a monopoly establishment in their designated area, and receive payment from CMS. OPOs found “not in good standing,” are referred to CMS (more on that below) for further investigation, but no OPO has ever been decertified as a result of this or any other complaint process. In fact, one of the OPOs that was designated “member not in good standing” went on to nearly kill a recipient of a uterine transplant because they failed to identify and flag a fungus on the uterus.124 UNOS did not disclose why the OPO initially received this designation, nor how and why it was subsequently restored to “good standing” status even despite this near-fatal patient safety lapse.125

People we spoke with said that cases that go through the MPSC generally focus on one-off failures, and that there is a missed opportunity to address the systemic issues. “I don’t think the OPTN has a means to look specifically at systems failure, and address them. The right answer is to look at a systems approach, rather than looking at individual events…One of the big flaws of the OPTN structure is that it has very little system approaches,” said one transplant surgeon.

UNOS says that their research department analyzes all submitted issues and delivers them to the OPTN Operations and Safety Committee (OSC).126 But one MPSC member we spoke with claimed the MPSC never talked to the OSC about system functions and systemic issues. The OSC has created suggested practices for all members to improve performance.127 However, these are largely voluntary. By UNOS’ own admission, “guidance from the OPTN does not carry the weight of policies or bylaws. Therefore, members will not be evaluated for compliance with this document.”128 As one person we interviewed put it, “the problem with OPTN policy is that it’s vague. It’s policy, but it doesn’t make anything black and white, it doesn’t truly give anybody anything to stand on when it comes to asking for enforcement of things.” As a smaller agency, HRSA historically did not seem to have the staffing capacity to deal with complaints. If someone complained to them, they turned it over to UNOS, illustrating the circularity of OPO oversight, as well as the regulatory capture, which has created the facade of oversight without any actual enforcement.

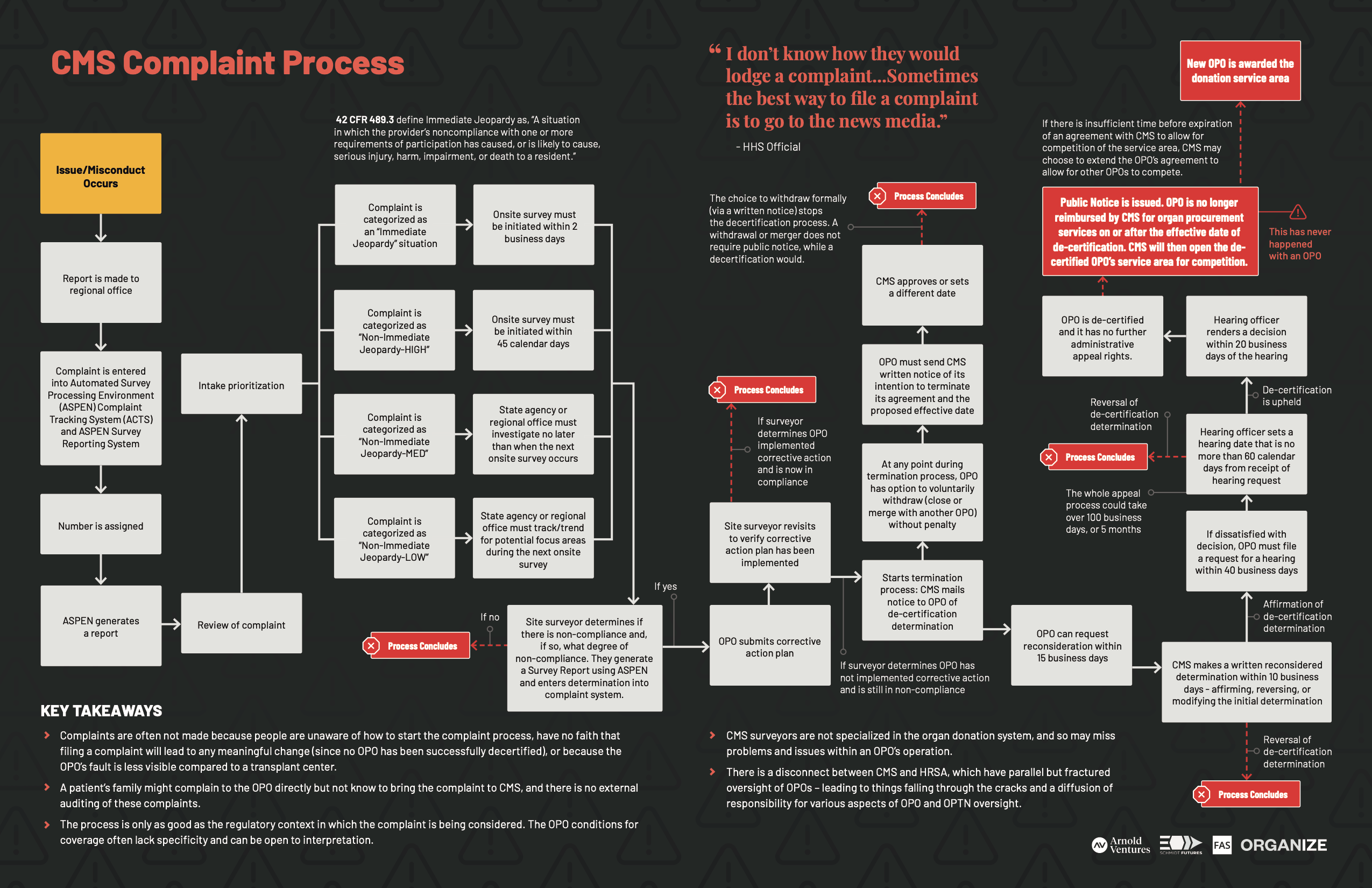

While very few people we spoke with knew about the CMS complaint process, a former CMS worker confirmed that there is a system for CMS to log complaints called the Automated Survey Processing Environment (ASPEN).129 CMS gives ASPEN access to select management and surveyors (Regional Office and State Agency) for use in managing complaints across all facilities including OPOs and Transplant Centers. When a complaint gets entered into ASPEN, Quality and Safety Oversight Group (QSOG) reviews and decides when and if to visit the site. QSOG then goes through steps to determine if the site is within compliance, and if not, it works with the site to get it back in compliance. (See CMS Complaint Map.) If the site fails to correct itself, CMS can ultimately create a public notice of termination, though that has never happened in nearly 40 years. Neither the public nor Congress has access to ASPEN, making it impossible to audit complaints filed and the manner in which CMS responded.

CMS Complaint Map

Download the “CMS Complaint Process Map” PDF

CMS intercedes when UNOS places an OPO on probation and/or finds them “not in good standing,” the latter of which, again, has only happened two times. In these instances, CMS cannot take action based solely on what UNOS finds; rather, CCSQ conducts a separate investigation into whether the OPO violated CMS regulations. According to an HHS official, CCSQ does not look at whether an OPO is operating efficiently or financially appropriately.130 The compliance aspects – from the CMS side versus the OPTN side – are largely divorced from each other. Most people we spoke with, both inside and outside of government, expressed little faith that filing a complaint would lead to meaningful change. In fact, no OPO has lost its government contract in the nearly 40 years the system has operated, including:

- the Miami OPO, Life Alliance Organ Recovery Agency, which failed to report a fungus in a uterus before sending it off for transplant, nearly killing the recipient;131 had a supervisor allegedly physically assault a nurse and doctor for speaking out against insufficient staffing and training;132 and was flagged in a peer review process for issues in management, staff training and collaboration with regional transplant hospitals133

- the Alabama Organ Center, whose leaders went to federal prison for receiving $500,000 in kickbacks from a funeral home134

- Kentucky Organ Donor Affiliates, which recovers only 1 in 4 potentially viable organs135

- the Los Angeles OPO, OneLegacy, which inappropriately spent taxpayer money on things like football tickets and parade expenses,136 was scrutinized by press for unethical tissue recovery practices137 and then tried to obstruct the Los Angeles Times investigation138

- the South Carolina OPO, We are Sharing Hope SC, which killed a lung recipient and injured a liver recipient by incorrectly identifying blood type and was later found to have problems with their blood-typing policies139

- Donor Network of Arizona, which took someone’s corneas without consent140

- Nevada Donor Network, which misled a donor family and “took more tissue than what was authorized” according to a lawsuit141

Two of these OPOs received a designation of “member not in good standing” by UNOS (Life Alliance Organ Recovery Agency and Nevada Donor Network) but the others have received no such designation or repercussions. Given UNOS and AOPO’s continued assertion that the success of the organ donation system relies on “maintaining public trust,” it is vitally important that the public have faith that OPO improprieties are identified and remediated.142

The ineffective complaint system and fear of retaliation results in a stagnant organ donation field that is more concerned with self-preservation and maintaining the status quo than improvement and innovation. This means that the 110,000 patients on the waitlist who desperately need more organs to be recovered will continue to suffer, and too many people, disproportionately patients of color, will die without the transplant they need.143

Transparency Around Conflicts of Interest

Nearly every person we spoke with alluded to conflicts of interest within the current organ transplant system. “The entire UNOS is a conflict of interest,” expressed one government official. Many of the UNOS board members are OPO leaders and transplant surgeons – representing the institutions for which they are making policies. Furthermore, many of the OPO leaders on the UNOS board come from underperforming OPOs, so there’s a disincentive to create stricter performance reviews. Of the nine OPOs represented on the OPTN/UNOS board,144 three are failing the new performance standards, including Iowa Donor Services which is notably among the worst performers in the country.145 Similarly, out of the several members on the MPSC who are directly connected to an OPO, nearly half come from an OPO that is failing the new performance standards.146

“The entire UNOS is a conflict of interest”

- Senior Government Official

OPO members on the MPSC were the ones who created UNOS’ OPO performance review process.147 Since underperforming OPO leaders are the ones creating their own performance review process, it’s essentially the “fox guard[ing] the hen house” as Senators Chuck Grassley and Todd Young wrote to the HHS Inspector General in 2019.148 Currently, the UNOS board has the same members as the OPTN board. This violates explicit direction from the Government Accountability Office (GAO), which in 2018 wrote that UNOS must maintain a separate board from the OPTN. The office explained its rationale, writing, “HRSA staff regularly observed instances where it was not clear whether the OPTN Board was acting on an OPTN-related matter or a contractor-related matter. The one-to-one correspondence between these boards amplified the lack of clarity.”149 150

Several people we spoke with explained that because it’s a small community, it can be hard to find subject matter experts to fill leadership positions without any existing conflicts. But, currently, the system requires an insufficient level of transparency around such conflicts. Thus, there is no pressure for individuals with conflicts of interest to make those interests transparent, or for the government or the public to evaluate the extent to which such policymaking processes are compromised by competing loyalties.151 According to one OPO CEO, “when OPTN Board members do disclose their conflicts of interest, it’s very informal. They talk about taking off their ‘transplant center hat’ and putting on their ‘OPTN hat.’ They know their interests compete, but they simply think they are entitled to the conflict.” In fact, as recently as September 2020, a Federal Judge ruled that emails between “UNOS decision makers and affiliates [showed] clear preferences for policy outcomes which the Court previously characterized as ‘arguable evidence of bias, or at least, individuals’ sporadic expressions of bad faith or agenda.”152 In UNOS’ response to the Senate Finance Committee oversight letter, they list the ways in which conflicts of interest are disclosed for the OPTN board and MPSC, yet it is questionable how effectively implemented these policies are, given we understand all disclosures are self-reported, and that the definition of such conflicts is often overly narrow.

Another version of opacity around conflicts of interests is the history of public comments made on the proposed rule and other Hill lobbying that were purportedly from unbiased third party medical professionals, but who were actually paid advisors to various OPOs. For example, the Connecticut and Vermont Medical Examiners provided comments arguing against death certificate accuracy for use in the proposed rule,153 an assertion upon which AOPO rested much of its opposition to proposed reforms. However, a Los Angeles Times investigation outlined how OPOs have co-opted medical examiners for lobbying purposes through direct payments and other gifts and event sponsorships.154

Similarly, AOPO cites “Emory Transplant Center” in their document against the proposed rule.155 However, this comment was actually written by an individual doctor who works at Emory and was paid $100,000 that same year as a board member of LifeLink Foundation,156 which operates three OPOs that were all considered failing in the notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM). This financial conflict of interest calls into question the motivation behind the doctor’s argument that closing failing OPOs would be too disruptive, given that, at the time this doctor submitted their comment, the OPOs compensating them appeared to be at risk of being decertified.157 LifeLink has subsequently come under Congressional investigation for various potential abuses, including its anti-patient lobbying tactics.158 This underscores the need for HHS and Congress to have more readily accessible visibility into the financial connections across the various transplant stakeholders that engage in lobbying and advocacy, including financial ties to OPOs or their partners, as well as the need for the ongoing Congressional investigation into LifeLink Foundation to assess the extent to which LifeLink employed such tactics in lobbying against HHS’ OPO reforms.

Finally, another theme we heard repeatedly was that individual OPO leaders are able to concurrently serve in multiple conflicting roles across the organ donation system, effectively consolidating power rather than checking it. For example, consider Alexandra Glazier, CEO and Board member of the New England OPO, which was highlighted in investigative reporting by the Project on Government Oversight (POGO) as one of the most aggressive OPOs in lobbying against HHS reforms for OPO accountability.159 Despite the OPO being the subject of an oversight investigation from the House Committee on Oversight and reform into potential conflicts of interest and anti-patient lobbying,160 Glazier serves in the following positions:

- Councilor on the OPTN/UNOS Board of Directors

- Chair of the UNOS Policy Oversight Committee

- a member (and past Chair) of the AOPO Legislative and Regulatory Affairs Committee

- a founding member of OPO lobbying group Organ Donation Advocacy Group

- a Board member of Donate Life America

- Member of the SRTR Review Committee

- UNOS MPSC, formerly

- UNOS Ethics Committee, former Chair

- Member of the UNOS Geography Committee161

- HHS’s Advisory Committee on Organ Transplantation (ACOT), previously

Even though this person is openly and actively lobbying against new accountability measures, she’s in a position where she can influence the very institutions that are supposed to keep OPOs accountable.162 Even though her influence is suspect, she’s serving positions where she’s supposed to:

- “lead the strategic coordination of national policy development” for OPTN/UNOS163

- set the lobbying agenda for two separate OPO industry lobbying groups

- advise the SRTR on how to risk-adjust data CMS relies upon to evaluate OPO performance

- influence national messaging around organ donation via Donate Life America.

Previously she advised HHS on OPO policy and until recently was involved in settling complaints about OPO misconduct for UNOS.

Additionally, senior staffers and board members at Glazier’s OPO serve as:

- Chairperson for the American Association of Tissue Banks (AATB) Board of Governors164

- Member of the the AATB Quality Council

- Chair of the Donate Life America Data and Research Committee

- Member of UNOS OPO Committee

- UNOS President, previously165

- Advisor to a current National Academy of Medicine study to, in part, “Consider the development of a new, standardized, objective, and verifiable donation metric to permit the transplant community to evaluate DSAs and OPOs and establish best practice.”166 While these various organizations can provide the veneer of independent validation, in effect there is often just a small group of individuals coordinating all efforts. According to an OPO employee we talked to, “One week we all meet at a conference for AOPO; the next week we meet at a conference for UNOS; and the next week we might be on some kind of OPO advisory committee for the American Society of Transplant Surgeons. But it’s all the same people, all we change is the letterhead for our statements.”

Communication Across a Diffuse Governance Structure